Don't be scared of the crazy landings you see on YouTube

This article originally appeared on the site in 2018. It has been updated with a reference to Storm Ciara and a new video, and republished.

You may have come across videos of seemingly crazy crosswind landings, like the ones in the clip below shot in Birmingham, Great Britain, where Storm Ciara has been wreaking havoc with the weather and bringing extremely strong winds.

The BHX airport is famed for its crosswind landing videos. AvGeeks regularly gather to shoot there on windy days. It looks terrifying, like a lot of those landings and takeoffs are perilously close to disaster. Spoiler: They are not. And we'll explain why.

"I've seen these videos, and sometimes non-aviation friends will tag me in them," said Shannon Pereira, a Boston-based first officer with JetBlue.

"Nine times out of 10, we're dealing with a crosswind," she said, noting that it doesn't matter if it's a takeoff or a landing. "And passengers won't notice. On approach, we are generally pointed in a different direction than perfectly parallel to the runway." This technique is called "crabbing into the wind," performed by pointing the aircraft into the wind just enough to keep the ground track aligned with the runway. Then, as they flare to land — raising the nose so that the main gear touches down first — the pilots will use the rudder pedals to align the plane with the runway's centerline. It's old hat for Pereira, who flies the Embraer E190.

"Obviously, you want to avoid those side loads on the landing gear, but the aircraft can handle it," she said.

Related: How pilots prepare to land during severe storms

The main landing gear of commercial passenger aircraft is locked in position with the longitudinal axis of the aircraft — the wheels do not rotate laterally to adjust for a crosswind landing. Several large aircraft such as the Boeing 777 and A380 have main landing gear that can rotate slightly on the ground for ease of taxiing, but not as crosswind compensation for landing. (The B-52 bomber's gear can adjust in the air and do just that.)

The View from the Flight Deck

The video below shows the view from the flight deck for a landing at Paris CDG. What's amazing about this landing is the amount of action on the control column. The pilot is calm, but he's also very focused on the physical task at hand. (You can see it in his face just prior to touchdown.) Pereira said that even though the control column will be moving this much, if you were watching it on the ground you wouldn't see massive adjustments in the plane's trajectory.

Wind Shear and Microbursts: The Bottom Falls Out on You

Wind shear is a change in wind speed or direction (or both) over a short distance. It can occur either horizontally or vertically and is most often associated with temperature inversions near the ground, strong surface winds, thunderstorms and rain showers. Wind shear on final approach is typically vertical wind shear. It's flagged for pilots by air traffic control, which has a low-level wind shear alert system on the ground at the airport. Other aircraft and in automatic local weather reports for pilots will also warn of wind shear, which is relatively common.

In the typical scenario with wind shear, the wind will suddenly drop off in speed, by as much as 30 knots. The plane's airspeed is measured by its speed relative to the wind, so losing 15 to 30 knots — up to 35 mph — in an instant is not pleasant. When it happens, it can feel like the bottom of the plane falls out from you.

"Wind shear makes a big difference at 100 feet," Pereira said.

"Where we know there is wind shear we'll change the power settings to add more power and less flaps, and come in at a higher speed," she said.

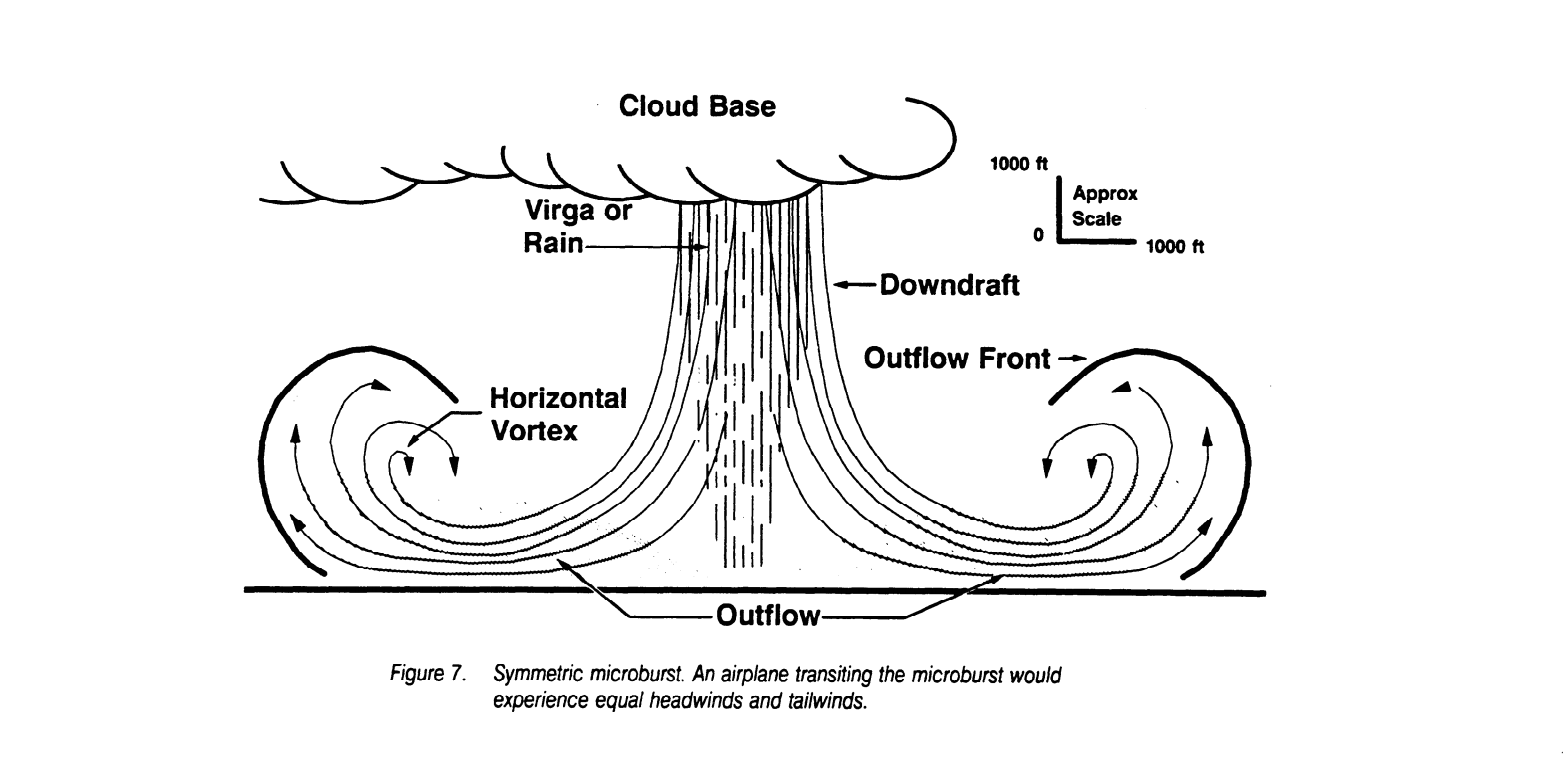

Since 1993, all US commercial aircraft are required to have a wind shear alert system installed, stemming from incidents related to a phenomena called microbursts. Microbursts are particularly dangerous concentrated downdrafts of air and have been the cause of numerous air disasters. In a microburst, a column of wind will descend rapidly over a small surface area, then hit the ground and push outward. The outward push causes a temporary increase in wind speed. But just as quickly, a plane passing through a microburst will hit a downward, violent and constant blast of wind, followed by a tailwind on the way out of the microburst. The consequence can be a loss of control of the aircraft. Fortunately, pilots and ATC work closely to avoid this possibility when landing, giving pilots time to anticipate and extricate themselves from problems.

The Go-Around

That's just what it sounds like: pilots can decide to stop the approach to landing and go around if they feel that conditions are unsafe.

"We do a lot of training in the simulators. When the time comes to go around, we're not shy," said Pereira. "We'd like to land the first time, but there will be good reasons to go around," she said.

Reasons include the aforementioned wind shear and microbursts, but also because of traffic on the runway or so-called "unstable" approaches, such as where the plane may be too high to descend at a reasonable rate.

Go-arounds can also happen because of loss of separation between the aircraft in front. "The DCA River Visual approach into runway 19 [at Washington National] is one such time where it can happen. There, it's one take off, followed by one landing. If we are gaining on the runway, the ATC will direct us to turn left or right and climb to a particular heading."

Go-arounds are ultimately a safety measure and not a cause for passenger concern.

"The captain has the final call on the go-around. The pilot flying should initiate the call. However, if the first officer is flying and the captain believes the situation unsafe or unstable he or she can call for the go-around and it must be initiated. Once a go-around is initiated you can't abort it," Pereira explained.

To make it easier, aircraft have "TO/GA" buttons on the throttles. Hitting the TO/GA switch — it stands for Take Off / Go Around — immediately increases engine power, allowing for a fast exit from whatever situation prompted the go-around.

Pereira speaks with the confidence of an experienced, well-trained pilot — one who knows that scary-looking landings are routine, but blue skies don't mean it's time to relax: "Pilots joke that if it's calm and clear out, that's when you'll have a crappy landing."

Mike Arnot is the founder of Boarding Pass NYC, a New York-based travel brand, and a private pilot.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app