How Windy Does It Have to Be Before Planes Can't Take Off?

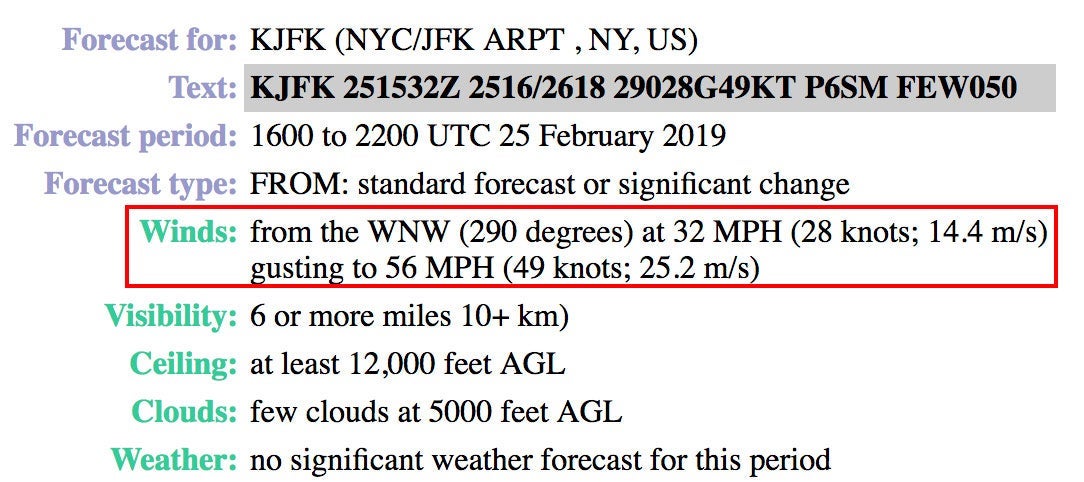

Severe winds have been gusting across New England and the mid-Atlantic, causing flight delays and even cancellations. At New York-JFK, pilots and airlines received this data to review during their preflight preparations:

The output shows plenty of visibility, blue skies and no thunderstorms (or snowstorms, for that matter). However, it's a touch windy, with gusts up to 56 miles per hour. That's going to stir up all sorts of dust and trash on the New York City streets. But for our pilots and their aircraft? It all depends on the aircraft — and the direction of the wind.

It's the Crosswinds That Pilots Look for

The real issue with wind isn't the speed of the wind per se — it's the component of the wind that's blowing across the runway in use. Planes like to take off into the wind, because it's the only thing in aviation that's free and provides lift. When air flows over the wings, flight happens, and the wind helps with that during take off.

Runways are designed and built to point into the so-called "prevailing wind," as determined by studies observing the wind in a particular area. You'll notice that at Los Angeles (LAX), every runway is pointing toward or away from the ocean. At Chicago-O'Hare (ORD), there are enough runways for air traffic control to adjust to many possible wind orientations.

Mother Nature, however, doesn't really care. She'll put the wind any which way, and in most cases at an angle to the centerline of the runway. The angle formed between the wind and the runway centerline is defined as crosswind. And there are limits to that component, as well as to tailwinds.

Every aircraft has its own stated crosswind limitations. The Boeing 737, for example, has a maximum crosswind component of 35 knots if the runway is perfectly dry, or 15 knots if the runway is wet. The larger Boeing 777 has a maximum crosswind component of 38 knots. This doesn't necessarily mean that the pilots and airport operations teams will decide to get underway if the winds are at those limits or close to them; airlines may very well impose lower crosswind limitations below the stated manufacturer's limits.

Airports, too can impose limitations. One widely-cited airport is London City Airport (LCY). There, the runway is only around 100 feet wide, compared to 150 or 200 feet at JFK. Accordingly, the maximum acceptable crosswind component is 25 knots.

"These calculations are performed on the airplane in our flight management system," a commercial pilot for a US carrier told TPG in an email.

"We have limitations on the aircraft that can't be exceeded. For instance, we have a limitation on my airplane that our maximum takeoff and landing tailwind component can't exceed 10 knots. We have one for [instrument approaches in low visibility] in which the maximum crosswind component is 15 knots," the pilot said.

"So, we input the weather and runway condition into the computer for the specific runway we plan to land on and the computer will come back with our landing speeds and the wind component for the runway. If it exceeds our limitations, then we don't attempt the approach or takeoff."

Calculating Limitations

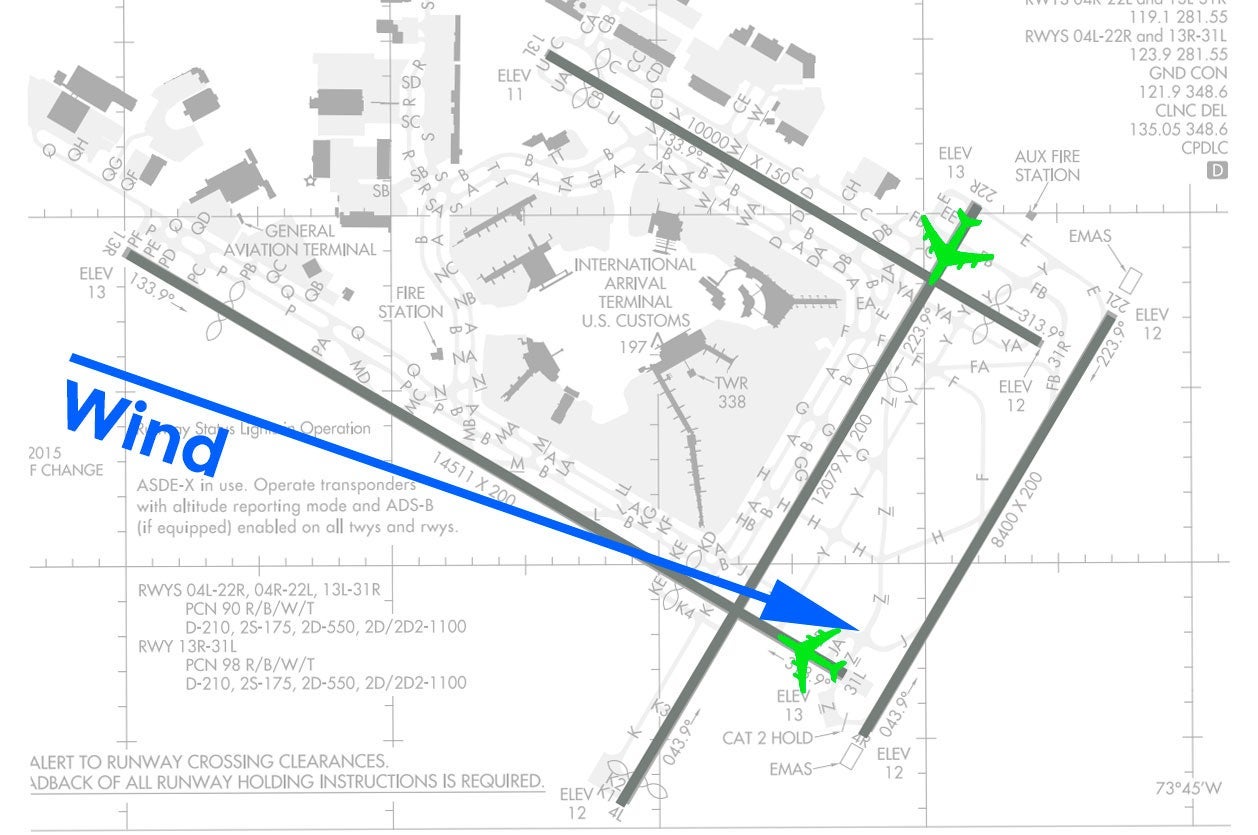

At JFK on Monday, at the time of this writing, the wind is coming from 290 degrees, and the runway in use for takeoffs is oriented to 310 degrees. (Without getting too much into the detail, the wind is displayed as a true heading, whereas the runway is oriented to a magnetic heading But I digress.)

Ignoring the gust factor for a moment, the headwind is 18 knots and the crosswind component is 10 knots. Even adding a gust factor of 49 knots — which is substantial — only 13 knots of that wind is part of a crosswind. The rest is just Mother Nature giving our aircraft more lift, more or less blowing straight down the runway. Our plane sitting at the approach end to runway 31L, at the end of the blue arrow, is ready to roll.

Now, let's say runways 31L and the parallel 31R were shut down for some reason, and the only available runway for takeoffs was runway 22R — where you see the second plane waiting to take off. That aircraft faces a crosswind component of 26 knots and a headwind of two knots — the wind is almost perpendicular and blowing hard. If you add the gust factor bringing this up to 49 knots, the cross wind component jumps to 36 knots, exceeding the limitations of the aircraft and likely far exceeding the limitations of the airline.

And what about even windier conditions?

Aircraft do have an additional limitation in terms of wind, and that is to open or close the aircraft passenger and cargo doors. Typically, the wind should not exceed 45 knots.

So why are so many New York City airports facing wind delays today? This is likely due to safety concerns for ground crew.

Mike Arnot is the founder of Boarding Pass NYC, a New York-based travel brand, and a private pilot who flies with a maximum crosswind component of only a few knots.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app