What are the strange noises and sensations you experience on a flight?

Flying is an odd concept. You turn up at a glorified shopping center to make your way down a narrow corridor into a massive metal tube with 300 other people. That metal tube is then pressurized, accelerated down a 9,843 foot strip of concrete and launched seven miles up into the air. You then spend the next 12 hours hurtling through the sky at 550 mph before two people who you've never met have the job of bringing that metal tube safely back down to earth.

And some of you choose to do this multiple times a week.

As pilots, we are quite aware of how alien the whole flying experience can be to some people. There's a whole range of noises and sensations which you'll only ever experience on an aircraft. Whilst these may not even be noticed by many, for a large number of people who have some form of anxiety about flying, they hear every chime and feel every bump.

Sign up for the free daily TPG newsletter for more travel tips!

At the gate

As you take your seat on board the aircraft, you suddenly become very aware of your surroundings. Settling down in an aisle seat, you're disconnected from the world outside and the visual cues which you normally rely on.

Bangs and knocks

Just as you're starting to relax, there's a huge bang under your feet and you feel the whole aircraft jolt.

As alarming as this may be, it's actually a very common sensation. Out of sight underneath the aircraft, ground staff are loading bags and freight into the aircraft cargo compartments, or holds. Suitcases are packed into special baggage containers which are then lifted up by large machines and slid into the hold.

Read more: 10 years of the Dreamliner — why pilots love flying the 787

Every so often, some containers are a little more troublesome than others, so the ground staff need to give an extra shove. As this container (sometimes weighing a couple of tonnes) is encouraged into the hold, it can often cause the whole aircraft to shake.

So the next time you feel this happen, remember that the holds are more than strong enough to withstand such knocks and it probably means that your bag has actually made it on board.

Engine start

Smoke from the engine

With the loading completed and the doors closed, it's time to push back from the gate and start the engines. Depending on the aircraft type (and outside temperature) this can either be done individually or in pairs.

As part of the startup sequence, the engine starts to spin up before fuel is added and the engine begins to run on its own. If you're sat by a window, you may notice smoke being emitted from the engine. If this happens, there is no need for alarm.

Read more: The 11 questions pilots get asked all the time

This will happen for a couple of reasons. Firstly, in between all long-haul flights, engineers will top the engines up with oil. If they happen to over fill it slightly, some of this oil will be burned off during the start process.

Additionally, if the outside temperature is very cold, some excess fuel may be burned outside the combustion chamber. This often looks dramatic as fairly large amounts of smoke can be seen blowing out the back of the engine, but this has no adverse effect on either the engine or the aircraft.

Flaps running

Once the engines have been started, we need to configure the aircraft for takeoff. Part of this involves setting the flaps.

The wing of an aircraft is designed to provide optimum lift during the high speeds of the cruise. To enable it to generate enough lift to take off, the shape must change in both surface area and angle. This is done by moving the slats on the front edge of the wings and the flaps on the rear edge.

As these are large parts, they need some strong forces to move them. In most commercial aircraft, the flaps are powered by the hydraulics system. As we select the flaps to the takeoff position, the hydraulic pumps in the belly of the aircraft come to life, pushing the slats and flaps out to the desired position.

With this movement comes some noise, often in the form of a whir, which lasts several seconds and can easily be heard in the cabin.

Takeoff

Quite often the most alarming time for people, takeoff can be an assault on the senses. As we move the thrust levers forward, the engine noise increases. There's a short pause to ensure they are all performing as expected and then we set takeoff power. Even though this is rarely the maximum power the engines can give us, you feel pushed back in your seat and the engines now seem to roar.

Bumps under the wheels

As we enter the runway for takeoff, we line the nose of the aircraft up with the centerline. Not only is this line painted on the tarmac but for operations in the dark, there are also lights fitted at specific intervals along the centerline. These are very much like the cats' eyes on a road and cause the rapid bump-bump-bump as we accelerate up to 190 mph before lifting off.

These lights perform two roles.

The first obvious role is so that we are able to see where the centerline is in the dark. With a strip of lights disappearing off into the distance, we can keep the aircraft tracking safely down the middle of the runway.

The less obvious use is to determine the visibility.

During operations in foggy conditions, certain criteria must be met in order for us to legally takeoff, normally a visibility of 410 feet. As each light is spaced 98 feet apart, if we are able to see five lights, we know that the visibility is greater than 410 feet.

Landing gear retraction

A few seconds after the aircraft lifts off the runway, we move the landing gear leaver to the "up" position. This action causes a number of things to happen.

Firstly, the doors which cover the landing gear bays open up. The movement of these doors into the airstream causes an increase in noise and airframe vibration. Next, the wheel brakes are applied, stopping the main wheels from spinning.

Now that the doors are open and the wheels have stopped spinning, the hydraulic system can activate, lifting the gear up in toward the aircraft. If you're sat over the main gear in the middle of the aircraft, you'll hear the hydraulic system whir into life and the big clunk as the wheels are locked up inside the gear bay.

If you're sat toward the front, you'll hear and the feel the nose wheel being retracted. This is particularly noticeable when sat in first class on many 747 aircraft as the nose wheel is right below the back row of the cabin.

Once the gear is stowed and locked, the gear bay doors close, returning the aircraft to its streamlined and quiet configuration.

Climb

With the gear retracted, we enter the climb phase of the flight.

Acceleration after takeoff

As we lift off the runway, we aim to pitch the nose up around 15 degrees to climb away from the ground at a safe speed, with the aim to reach 1,000 feet as quickly as possible. This ensures that we get clear of any obstacles like cranes or radio masts, but also reduces the noise for people living around the airport.

Once at 1,000 feet, we don't need to climb quite so quickly, therefore at this point we do a couple of things.

Firstly, we pitch the nose down to around 10 degrees. This allows the aircraft to accelerate so that we can retract the flaps and move toward the climb speed. This reduction in pitch angle makes it feel like the aircraft is dropping. However, this is not the case. All that is happening is that the climb rate is just reducing whilst the aircraft accelerates.

At the same time, as we don't need so much power to continue the climb, we reduce the engine power. Depending on the aircraft type and where you're sat, this change in engine noise can be quite profound. It sounds as if the engines have just failed but I promise you that this isn't the case.

Changes in engines power

As the aircraft continues its climb toward the cruising altitude, you may notice that every so often the engines reduce in noise before roaring back to life a few moments later. This isn't the pilots having problems with them but what is known as a '"step-climb."

Airspace around certain cities, London in particular, is a highly complex and busy 3D jigsaw puzzle. With this in mind, very rarely are we able to climb straight to our cruising altitude but instead we must perform a number of step-climbs.

Each time we level off at an intermediary altitude, the engines power back so that we maintain our speed. When we are given clearance to climb again, the engines power up to enable us to start the climb.

Once again, it may sound dramatic sat in the cabin but it's all completely normal.

Cruise

Once up in the cruise, the atmosphere in the flight deck relaxes a little whilst the cabin crew burst into life to begin the cabin service.

Chimes

When working in a large office, which is what the aircraft is to us, communication isn't as easy as just yelling at each other. As a result, aircraft have a network of interphones, which allow crew to call any other phone.

Like with your phone, when someone is trying to contact you, it rings — and this is what the chimes are that you can hear in the cabin. When you see a crew member answering the phone, it's not because there is a problem with the aircraft, more likely that the crew member at the back has run out of chicken meals.

Descent

With the end of the flight approaching, it's time for us to bring you safely back down to earth. The engines are brought back to idle power and we effectively glide down toward the runway. However, sometimes even this isn't enough. Energy management is key during the descent and approach and so drag (not the fancy dress and makeup kind) is our best friend.

Speedbrake rumbling

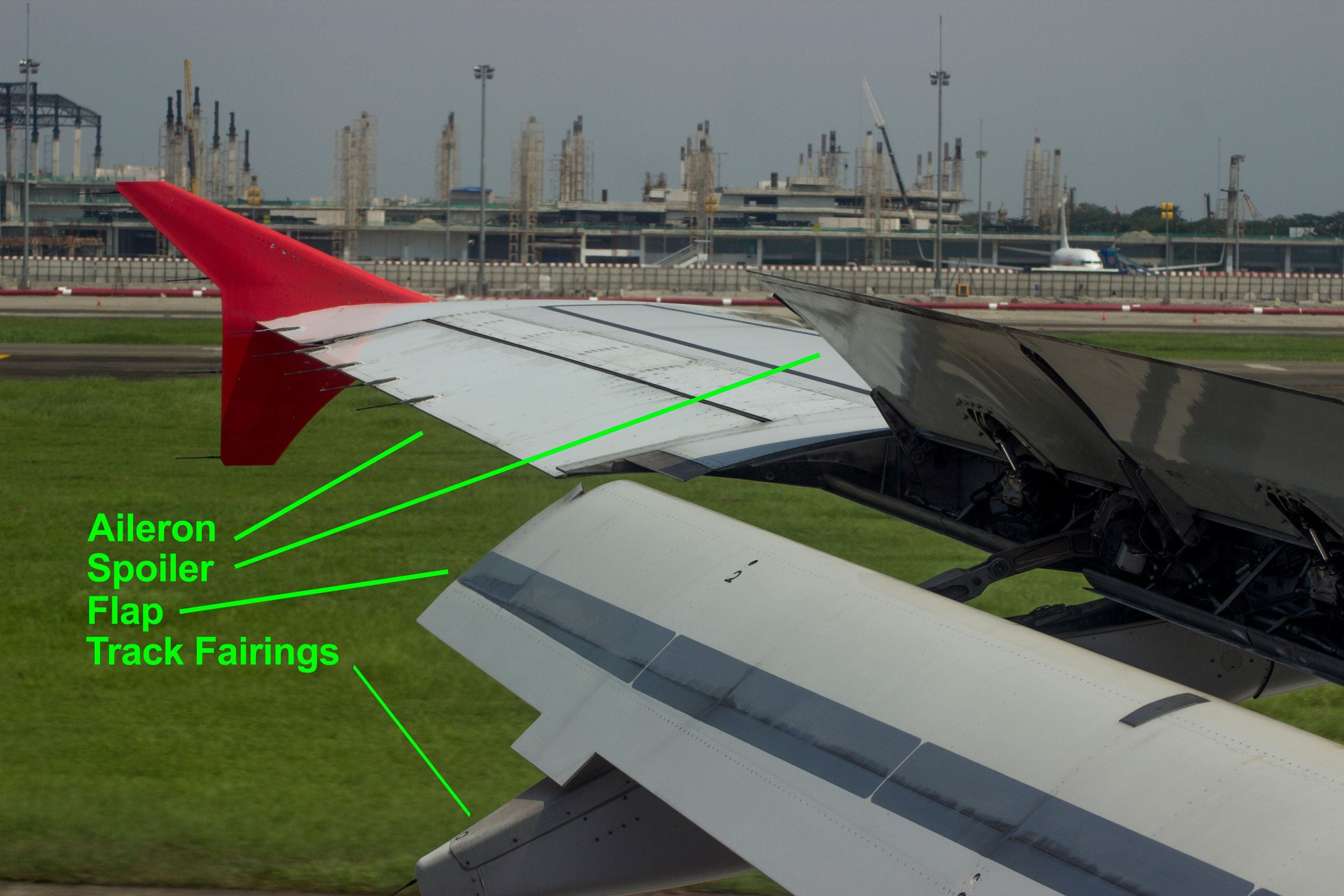

Have you ever suddenly felt the whole aircraft shaking and with it the aircraft start to descend quicker? Next time this happens, and you're sat by a window, take a look at the wing.

You'll notice large panels on the top, sticking up into the airflow. These are known as spoiler panels as they literally spoil the airflow over the wing, reducing the lift and allowing us to descend quicker. These are particularly useful if we are high on the approach profile, either because ATC kept us high to keep us clear of other traffic or they have given us a short cut and have reduced our distance to land.

Either way, they are a great tool to help us manage the energy of the aircraft and not something that you should be worried about.

Landing

The favorite time of the flight for pilots, mainly because it's the most rewarding but also partly because it means that our bed is not far away.

The touchdown

Contrary to common belief, a firm touchdown is not necessarily a bad landing. When the runway is slippery, or there are strong winds, we aim to land the aircraft positively onto the runway.

By touching down in the correct part of the runway and allowing the speedbrakes to deploy, the weight is transferred onto the wheels, allowing the brakes to safely decelerate the aircraft. The quicker this process happens, the quicker we stop.

Reverse thrust

The other important part of the landing roll is the reverse thrust. By redirecting the flow of air from the engine forwards, it acts like another braking system. That said, it is most effective at high speed, hence why we activate the reverse thrust as soon as we touch down.

The sound of this can be quite loud, especially if you're sat just in front of the engines. Once again, this is a normal part of the landing roll, ensuring that the aircraft comes to a safe stop on the runway.

Bottom line

Flying can be quite an assault on the senses with a whole host of noises and sensations causing alarm. However, all these are totally routine for a normal flight. With a little knowledge, you can understand what are these things are and realize that they are completely normal for a flight.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app