Airbus A321LR versus the Boeing 787 Dreamliner: Which do pilots prefer for transatlantic flights?

Last month, JetBlue launched its inaugural flight between New York-JFK and London Heathrow (LHR) on an A321LR aircraft. Narrowbody aircraft are nothing new to transatlantic travel, but JetBlue's entry into the highly competitive New York to London route caused quite a stir.

For travelers sitting in the cabin, the experience is comparable with other transatlantic carriers, with lie-flat seats in business class and mood lighting and amenity kits for passengers in the back. But how does transatlantic flying in an A321 differ from a 787 Dreamliner for the people sitting farthest forward — the pilots?

In my career, I've spent just over 3,000 hours flying the A321 (7,000 hours total with the A320 family) and nearly 4,000 hours flying the 787 Dreamliner. As a result, I feel I'm in a good position to compare and contrast how it feels to fly the two aircraft, particularly on routes with longer flight times.

Each aircraft has its own little quirks, some of which many pilots like, others which pilots may not prefer. It's like the difference between driving a Mercedes and BMW: They both offer quite a different driving experience, but ultimately either will get you safely to your destination.

Airbus A321LR versus the Boeing 787 Dreamliner

787 Dreamliner

Starting with my current ride, the 787 was made for long-haul flight with a range of 7,500 nautical miles. It was the aircraft selected by Qantas to fly the first-ever direct flight between Australia and the U.K., a 17-hour epic from Perth Airport (PER) to London Heathrow.

The 787 is a widebody aircraft, meaning there's enough space in its 18-foot-wide cabin for two aisles. It has a wingspan of 197 feet and has a length of between 187 feet for the 787-8 to 223 feet for the 787-10. It has three fuel tanks, enabling it to carry more than 100 tons of fuel, allowing it to fly nonstop journeys between cities such as Perth and London and Sydney and New York.

Airbus A321LR

The A321LR is a descendent of the original A321, a variant of one of the most popular aircraft ever built for the short-haul market, the A320.

By adding extra fuel tanks, it has a range of 4,000 nautical miles, meaning it is able to comfortably fly routes such as London to New York City, and Miami to most of South America. As a result, it is an extremely attractive option for not only established long-haul carriers but also short-haul airlines looking to expand into lucrative intercontinental routes.

One of the main advantages for airlines is that it requires very little extra training for their crew. Pilots already rated to fly the A320 family can fly an A321LR without the need for the long (often three-month) conversion course required to move onto a larger aircraft like the 787.

The A321 is considered a narrowbody aircraft, meaning that the 12-foot-wide cabin is only wide enough for a single aisle. It is also somewhat smaller than the 787 with a length of 144 feet and a wingspan of 118 feet.

Ergonomics

To the outsider, the flight deck of an A321 and a B787 are quite similar. However, when you spend thousands of hours sitting in them, you become very aware of the similarities and differences.

The most obvious difference is that the A321 has migrated to using a sidestick located outboard from the pilot, whereas the B787 still has a traditional control column situated between the pilot's feet.

Both have their advantages, but I'm going to get off the fence here and declare that I prefer the Airbus setup, particularly for long flights.

The flight deck of an aircraft is basically our office. Not only is it our office, but it's also our dining room and our lounge. It's where we can sit for nine to 10 hours in a single stretch, so the more ergonomically designed and comfortable it is, the better we will perform.

The control column on the 787 is great for flying the aircraft, but most of the time we engage the autopilot a couple of minutes after takeoff and then leave it engaged until a few minutes before landing. With the autopilot engaged, we have no use for the control column. This would be fine on a short flight, but when we're sitting for hours on end, it just gets in the way.

You'll see most Boeing pilots with a clipboard for their inflight paperwork. This is because there are few places to store it and, more to the point, it is difficult to write with the control column in the way. As a result, we use a clipboard to keep the paperwork together and to provide a flat surface on which to keep a track of our route and fuel status.

It is also difficult to eat your food properly as you can't fit the tray onto your lap without moving the seat back away from the controls. As a result, to ensure that one pilot is able to reach the controls at all times, we sometimes have to take it in turns eating.

On the A321 however, the position of the control stick to the side of the pilot means Airbus has been able to install a fold-away tray table. Once airborne with the autopilot engaged, just like on the 787, the pilots are able to pull out the table and use it to complete their paperwork and eat their meal, just like being at a proper desk or table.

The absence of the control column also means it's much easier to get comfortable in the seat as we are not restricted as to where our legs can go.

Winner: Airbus A321LR

Ride Comfort

We've all been there: Just as the meal service starts, the bumps begin. As you try to take a sip of your red wine, a jolt forces the glass against your chin and its contents into your lap. For most people, turbulence is just an inconvenience, while for others it's a real fear.

Turbulence is caused by variations in the wind speed and direction hitting the aircraft and affecting the lift over the wings. An increase in wind speed creates more lift, a decrease created less lift. Multiply this hundreds of times a second and you get what you experience as turbulence.

In order to counter this, designers at Boeing utilized a number of sensors around the 787, which detect and measure changes in angular velocity and air pressure. Lateral gusts of turbulence causing wind are recorded by gyroscopic sensors and vertical movement is recorded by accelerometers. Changes in air pressure around the aircraft are also detected.

All this information is sent to central processing computers which, in a fraction of a second, calculate not only what is happening to the aircraft but also what needs to be done to counteract those movements. The computers then send electrical signals to the actuators powering the control surfaces on the wings and tail to counteract the forces the aircraft is experiencing.

The result is that, as the aircraft instantly reacts to the turbulence-creating forces, the bumps you feel in your seat are reduced and feel much less significant than they would on, say, the A321.

Winner: Boeing 787

Air Quality

The A312 uses what is known as 'bleed air' to pressurize the cabin. As part of the engine operation, some air is 'bled' out of the high-pressure compression stage and then fed into the air conditioning system. This air is then used to pressurize the aircraft and keep the cabin at a comfortable temperature.

This is a tried and tested method that works well across all aircraft types, ever since the first pressurized aircraft took to the skies. But on the B787, things are different.

Instead of taking air from the engines, fresh air is drawn in directly from outside the aircraft, forward of the engines, by two dedicated inlets on either side of the aircraft. This means the air that we breathe inside the aircraft is fresh from outside and hasn't been through the engine.

Not only does this mean that inside the cabin the air is of much better quality, but it also means there are savings to be made externally. As high-pressure air in the engines is not feeding the air conditioning system, all of it can be used to generate thrust. This means that the engines are not wasting airflow, making them much more fuel-efficient and thus reducing carbon emissions.

Winner: Boeing 787

Performance

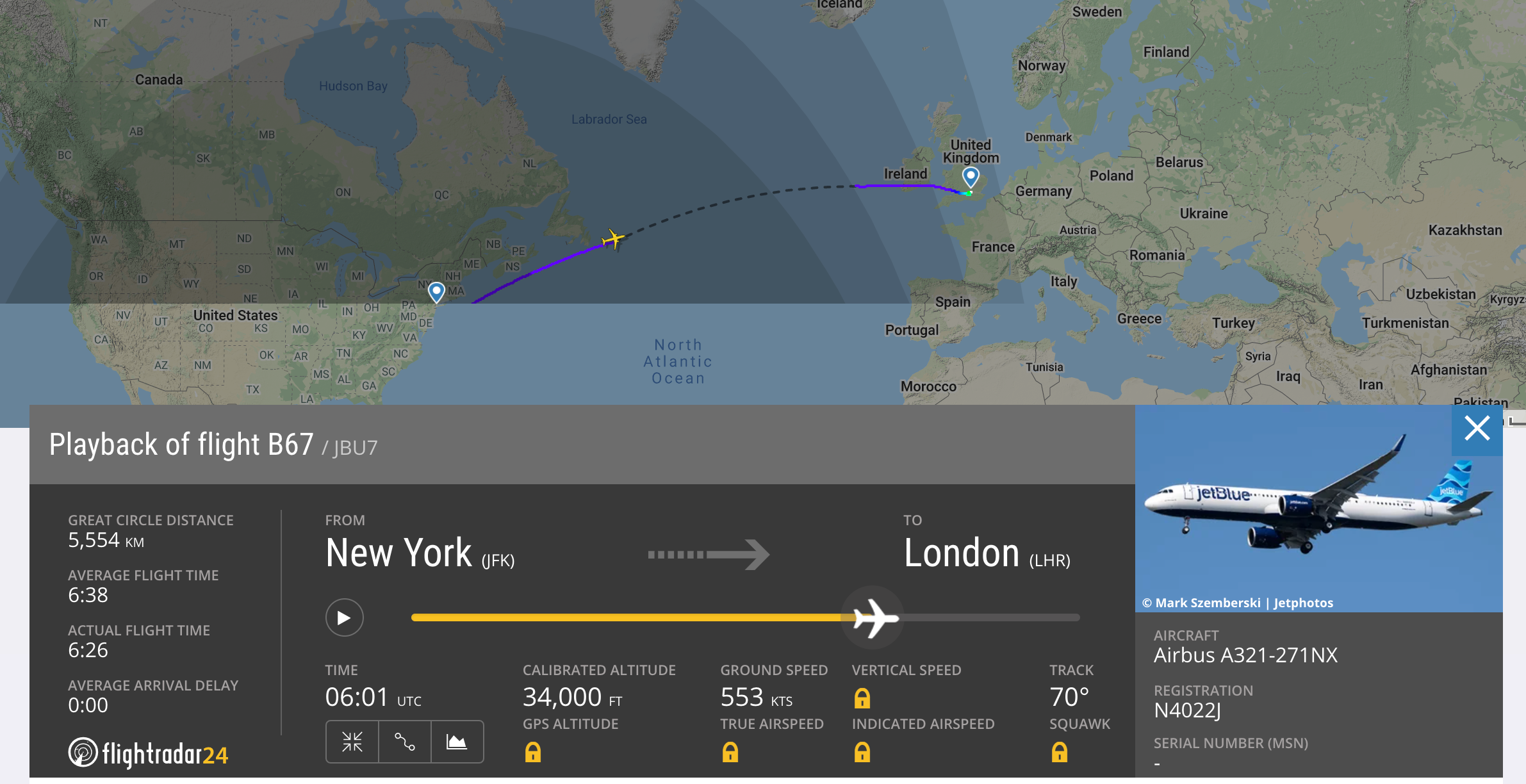

Whilst the range of the A321LR has been increased by the addition of extra fuel tanks and tweaks to the wingtips, the wing on the A321LR is very similar to that of the original A321. As a result, particularly at heavy weights, the aircraft is quite limited to how high it can climb, as can be seen in the image below.

However, the wing on the 787 is an incredible feat of engineering. If you watch the video below, you'll have noticed just how much the wings flex as they are creating lift. This design enables the aircraft to climb to higher altitudes for a given weight than most other aircraft types.

This benefits us in a couple of ways. First, it means we can often fly above turbulence. There has been many a night flying across the Atlantic where pilots in aircraft below us at 33,000 to 37,000 feet have complained about the bumpy flying conditions while above them, at 43,000 feet, we've had a smooth ride.

Secondly, by flying higher than most other traffic, it means we are more likely to get shortcuts. As air traffic is a giant three-dimensional puzzle for Air Traffic Control (ATC), when you have more aircraft at a certain altitude, there's less opportunity for them to deviate from their planned route.

When there are fewer aircraft at your altitude, ATC can often let you fly more direct routes. This not only saves fuel but also time.

Winner: Boeing 787

Technology

Whilst the A321LR is a relatively new aircraft, it is a variation of the original A321. As a result, most of the flight deck technology is very similar to that of the original creation. However, the 787 is an aircraft designed for the 21st century and therefore has a number of technological advances which help improve flight safety.

One of the most useful features is the Head-Up Display, or HUD.

Part of learning to fly a jet aircraft is mastering the ability to flick between scanning the vital flight parameters such as altitude and speed inside the flight deck and viewing the visual picture outside the aircraft. During an approach, a pilot's eyes will constantly be darting between the two.

However, for a while now, technology has existed in military aircraft that allows pilots to continue scanning the flight parameters whilst still looking outside — it's called a Head-Up Display. A projector is fixed to the ceiling above the pilot's head and from it projects an image of the Primary Flight Display (PFD) onto a piece of glass in front of the pilot.

Whilst this feature is great during most stages of flight, it really becomes important during the approach and landing. Some approaches require pilots to fly tight turns very close to the ground, often in marginal weather conditions. The approach to Runway 13L at New York's JFK is a great example of this.

When we fly this approach, we need to keep our eyes on the runway as much as possible. The HUD enables us to do this whilst still scanning our altitude and airspeed as we fly the tight turn around the corner, as can be seen in the video taken in the simulator below.

Winner: Boeing 787

Bottom Line

Whilst both aircraft are capable of flying long-haul routes, as a pilot, my preference would be to do so in a 787 Dreamliner over an A321.

The flight deck of the A321 is definitely more practical for longer flights with the tray table making the flight deck much more comfortable and usable as both an office and dining room.

However, the A321 is still very much a short-haul aircraft updated for long-haul flying.

The 787, on the other hand, was designed specifically for long-haul routes. The performance of the wing and features such as the gust suppression system and non-bleed air conditioning mean the entire experience of a long flight is made much more comfortable for everyone on board.

As a result, both passengers and crew get off the aircraft feeling much more refreshed and less tired than they would expect.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app