What Are Airplane Windows Made of? (And What Is That Little Hole?)

When you're in flight, the only thing separating you from the minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit and unbreathable, thin air outside is an airplane window. On one side, there's a warm, pressurized cabin where you can work, watch movies, sleep — and on the other, a world that would kill you in minutes if you were exposed to it. Between the two, just incredibly sturdy windows. A very exciting subject for AvGeeks, but maybe a bit of a mystery for the flying public. So, let's take a deep dive into aircraft cabin windows and flight deck windshields.

Cabin Windows: No, They're Not Glass

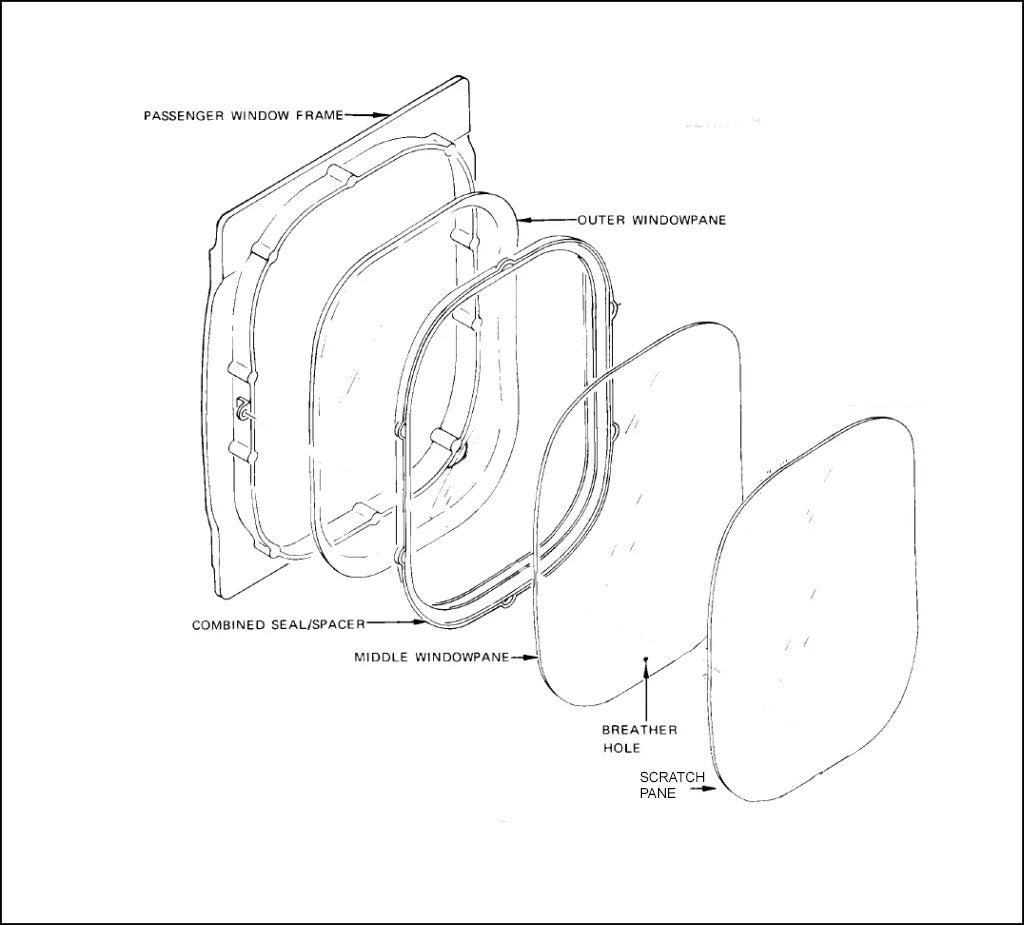

A cabin window consists of three panes: 1) an outer pane flush with the outside fuselage, 2) an inner pane — which has a little hole in it you may have spotted, and 3) a thinner, non-structural plastic pane called a scratch pane. Passengers can't touch the inner pane (the one with the hole in it) or the outer pane, for safety reasons. Instead, passengers can rest their weary heads against the scratch pane, press their iPhone against it, or simply muck it up with greasy fingers. The scratch pane isn't actually part of the window assembly itself, but installed separately.

The main thing to know is that aircraft cabin windows are not made of glass, but with something called "stretched acrylic". It's a lightweight material manufactured by a few global suppliers for the various aircraft flying today. One such supplier is UK-based GKN. The largest manufacturer of cabin windows worldwide, GKN makes cabin windows for the Boeing 737 and the Boeing 787, and most other aircraft.

"Stretched acrylic is produced by stretching the base material of as-cast acrylic. It provides better resistance to crazing [hairline cracks], reduced crack propagation and improved impact resistance," said Jason Webb, Director of Business Development and Aftermarket Services at GKN in California, in an email.

The inner and outer pane thickness is specific to each type of aircraft. "Inner panes are generally thinner at approximately 0.2" thick and are only present as a fail-safe if the outer pane fails," said Webb. This is a very rare occurrence, most notably with Southwest Flight 1380 — which was actually a failure of the engine, not the window.

"The outer panes are thicker at approximately 0.4" thick and carry the pressure loads for the life of the window," Webb said. The increased thickness is meant to "to allow for engagement with the airframe structure while maintaining the required strength. The air gap is approximately 0.25" and also varies for each aircraft," Webb said.

What is the little hole for?

As your flying tube gains altitude, the pressure acting on the outside the plane drops — the air is much less dense the higher your plane climbs. Because aircraft cabins are pressurized to about 6,000 feet for passenger comfort (and survival), there is more pressure inside the plane than acting on it from the outside. That pressure is bearing on the fuselage and the cabin windows. The little hole on the inner panel allows some of the cabin air to escape into the pocket between the inner and outer panes and equalize. This forces the outer pane to take all of the load, albeit slowly. It's a tiny hole so that as the plane ascends, the pressure slowly equalizes.

The scratch plane covering the inner pane doesn't block air from escaping into the hole. "It's not airtight. Air can flow into that space through multiple gaps in the interior wall assembly," Webb said.

Frost can form on the inner pane because moist air from the cabin seeps through the hole as the aircraft gains altitude. It freezes on contact with the very cold windows.

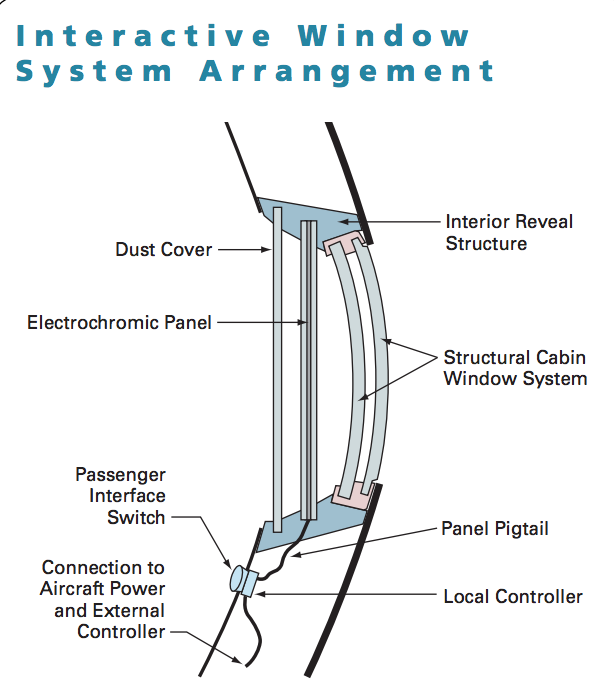

The marvel of Boeing 787 windows

If you've flown on a Boeing 787 Dreamliner, you know the windows are a cut above. First, they are quite a bit larger than most airline windows, at 19 inches high. The structural cabin window is made by GKN, as noted above, with the familiar inner and outer panes made of stretched acrylic.

However, unlike other planes, Dreamliners do not have a physical window shade. Instead, the shade is controlled by magic: electrochromic technology which uses electricity to change the color and amount of light that passes through the window. It does this by means of a medium, a gel, that darkens or lightens depending on the charge. This system, branded as Alteos, is manufactured by US-based PPG Aerospace using technology developed by Gentex, based in Michigan. "Applying a small electrical voltage across the gel causes it to darken, while removing the voltage allows the gel to return to its natural transparent state. The voltage can be precisely controlled and adjusted in small increments to allow intermediate states of light transmittance to be selected," is how PPG explains it.

Below, windows are darkened in a 787 cabin, except for the two at the back.

The results are amazing: I flew the Dreamliner with JAL recently, and the cabin was dark enough for people to sleep comfortably with the windows at the darkest setting for people could sleep. Nevertheless, even with darkened shades you could tell it was bright and sunny out as we passed over the Canadian Arctic. Trippy.

The window has no moving parts, operates silently, and goes to transparent in the event of loss of power. According to PPG, the electrochromic windows block 99.997% of the visible light.

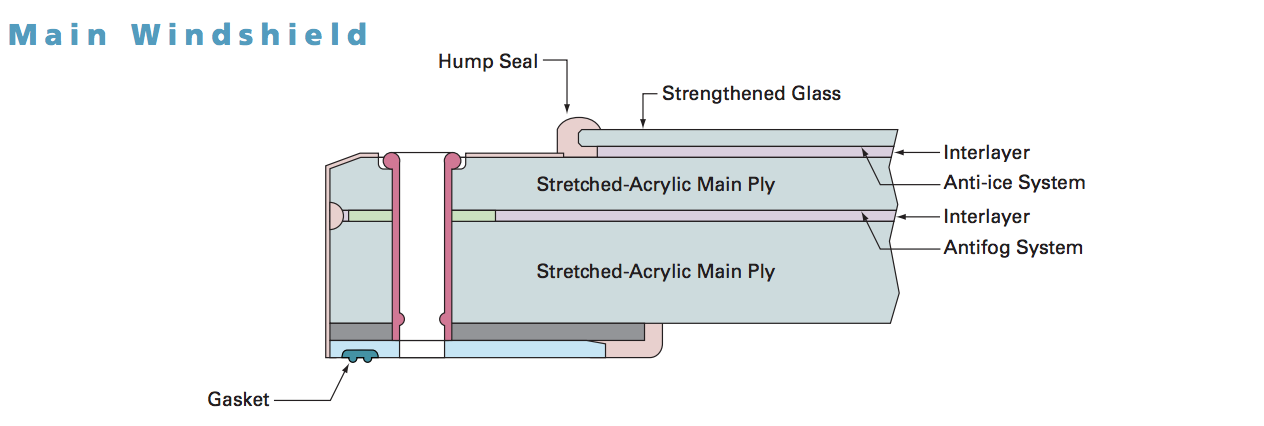

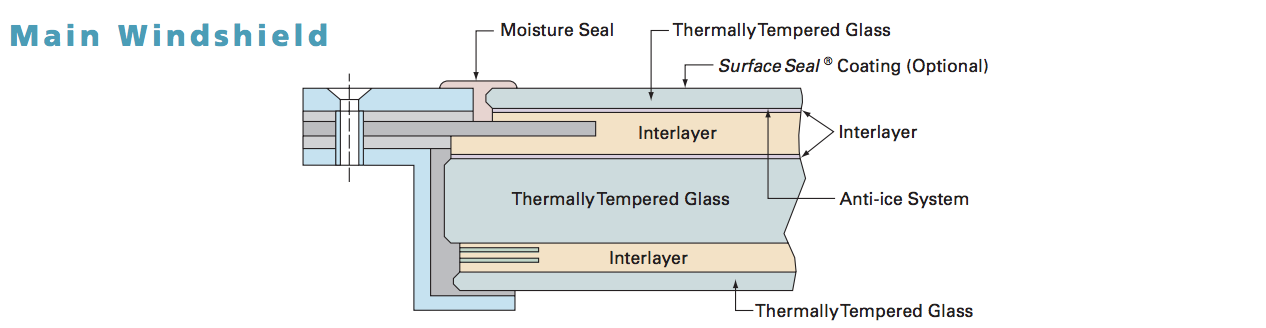

Flight Deck Windshields

Unlike cabin windows, the flight deck windshields are made with glass-faced acrylic — an outer layer of glass bonded to stretched acrylic. Then, there's a layer between them, made of urethane. Each has anti-ice and anti-fog systems. In the case of the Boeing 787, there are then layers of stretched acrylic, just like the cabin windows, albeit much thicker — between one and three inches thick depending on the aircraft.

In some cases, such as the Boeing 737 and Boeing 747, the windshield features two plies of tempered (i.e. hardened) glass along with an interlayer. This design is likely a throwback to the originally-approved designs, with the Boeing 787 sporting a lighter version with an outside, tempered glass ply.

Have you ever noticed that the cockpit windshields sometimes look like they have oil on them? That oily sheen is actually a coating of indium tin oxide, which is a conductive material between the layers and transmits heat. Accordingly, this thin coating is all that is needed to keep the windows nice and clear in frosty weather. Brilliant.

According to PPG, in the past "this was accomplished with thin wires of a design similar to those in rear car windows, but the main manufacturers now use a coating of indium tin oxide. Just nanometers thick, this coating sits between glass plies and is completely transparent."

What About Bird Strikes?

Bird strikes are a cause for concern for pilots, airlines and manufacturers. Accordingly, flight deck windows are rigorously tested by the manufacturers. Federal regulations in the US require the window panes "withstand, without penetration, the impact of a four-pound bird when the velocity of the airplane" is equal to around 340 knots indicated airspeed in the case of a 737. (That is quite fast.)

Below, you'll find a video of a birdstrike on a cockpit windshield which occurred less than 100 feet off the ground, just prior to landing. As you can see, this startled the first officer. The bird makes a solid thwack against the windshield but the aircraft goes on its merry way. Not so the bird, sadly.

Mike Arnot is the founder of Boarding Pass NYC, a New York-based travel brand, and a private pilot.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app