How Pilots Land Airplanes at Night

Flying at night is one of life's great pleasures. I personally like to press my nose against the window and watch the incredible views. Night flight has even inspired books such as, well, Vol De Nuit,

But is it any more challenging for pilots to land their giant, heavy aircraft at night?

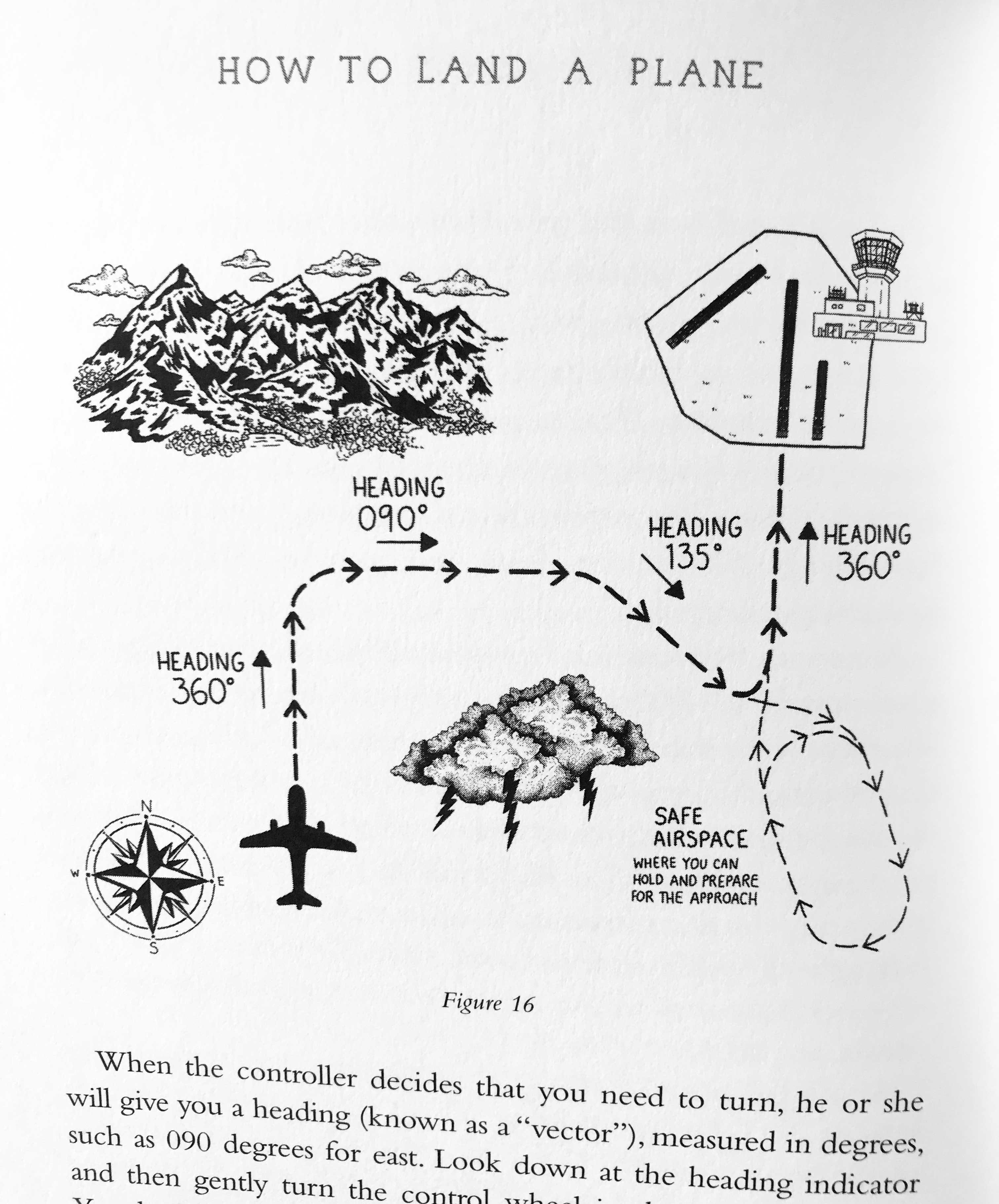

No, said Mark Vanhoenacker, a British Airways Senior First Officer in an email to TPG—perhaps anti-climatically. Vanhoenacker is the author of Skyfaring, the popular book every traveler should read. Later this month, the BA Boeing 787 pilot will release a new book in the US called How to Land a Plane which does quick work of explaining the complexities of flying and landing, along with simple illustrations to clarify.

"In some ways, it's more straightforward to land at night, because the runway lighting systems are so clear and bright, and the areas around runways are comparatively so dark," he explained.

"It's easy to think of airports as very well-lit places," Vanhoenacker said. "But when we are looking out the cockpit window at a cityscape, the airport may well be one of the darkest parts of the view. Taxiway lighting, for example, is quite subtle until you're close to it—which helps keep our eyes acclimated to the night world. Looking out at night across a large and well-lit city, the darkest region you can see may well be the airport itself."

"I haven't noticed a huge variation between airports," he said, noting that environmental differences play a role. "I can remember differences, certainly, between approach lights in Phoenix on a clear winter night, and those seen in hazier, far more humid Hong Kong in the height of summer."

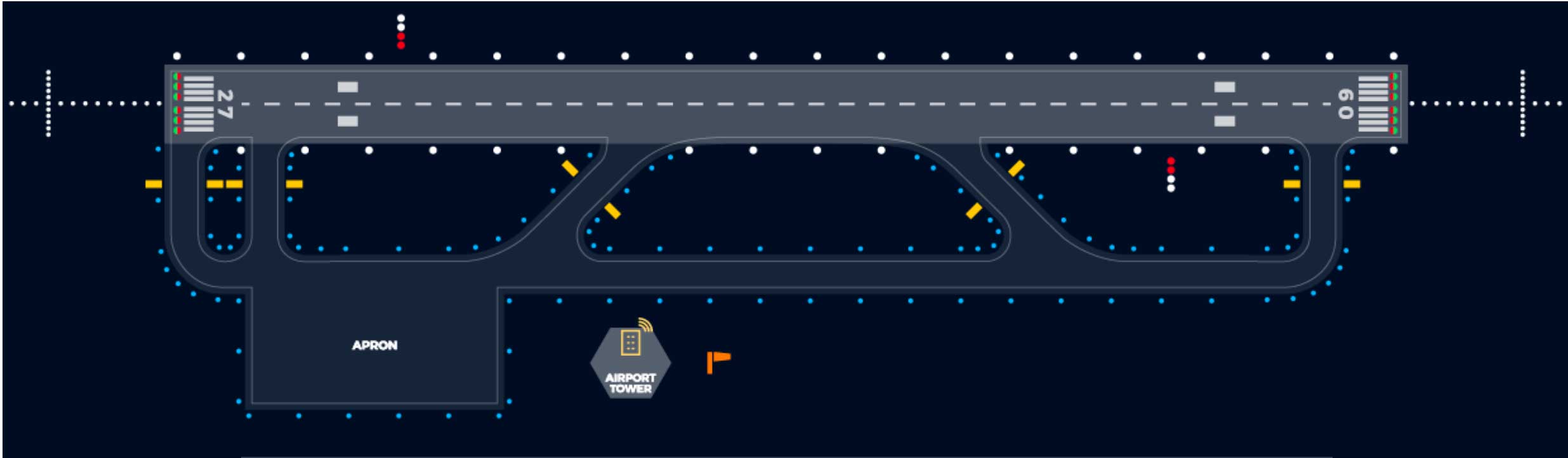

The airport lights themselves — and there are a dozen or more combinations of signs, lines, lights and colors — are beyond the scope of this article. At its most basic, the runway is lined by white lights for most of its length, called the runway edge lights. The taxiways, in contrast, are lined with blue lights. Pilots don't want to be lined up to land on a blue-lit taxiway, although it does happen occasionally.

The image below is a good representation of the runway lighting system. (You can turn off the lights and explore at this link.) The white and red lights adjacent to the runway, called PAPI, let pilots know if they are too high or too low on approach, depending on the angle between the lights (which are always on and used during the day as well) and the plane's glideslope. If you're too high, you'll only be able to see the white lights. If you're too low, you'll only see the red lights. The objective is two red lights and two white lights, as seen here.

Vanhoenacker explained that certain approaches to landing are specified as "day only," as well as entire runways. "The main airport in Hyderabad, India, for example, has one primary runway, which can be used at any time, but also a secondary, backup runway which is specified as usable only in daylight."

Aircraft lights

"You can divide an aircraft's lights into two categories: those that are designed to help you be seen, and those that are designed to help you see," Vanhoenacker said.

"In the former category are things like navigation lights, which are arranged on aircraft just as they are on ships — one more example of aviation's deep nautical roots. Among the latter are landing lights, which are very bright indeed," he said.

"We use these for take-off as well as landing. And some of the landing lights are usually on for all flying when we're below 10,000 feet. Some are mounted in the wings and some are in the nose landing gear (so those can't be used until the gear is lowered, of course)."

"Another subtlety of landing lights is that they point out and down at a very specific angle, which is determined by the geometry of the aircraft when it is in its landing configuration on final approach. So the lights are looking down as well as forward. In How to Land a Plane I talk about how a plane is often not pointing in the direction it's moving — even when we're landing, the nose is pointing upwards — and the careful placement of the landing lights accounts for that."

When it comes to the approach to landing, Vanhoenacker explained that it is typically done by reference to on-board instruments.

"We have either instrument approaches (a radio navigation aid that's broadcasting from the ground) or newer guidance systems (such as "RNAV" approaches which may be contained entirely in the aircraft's own systems, without any ground-based aids) to back up what we can see out the window," he said.

"The approach lighting is so good, often extending for hundreds of yards before the runway itself, even if that means building piers out into the water around the airport to hold the lighting apparatus, as at SFO and JFK."

What about at night, in the fog?

"In general, landing minima — the lowest altitude or height we can descend to without seeing the runway or its lights with our own eyes — isn't affected by the time of day," Vanhoenacker explained.

"The visibility — measured by those two curious, periscope-like contraptions you may see, pointing at each other next to the runway — determines whether we are permitted to make an approach. Then, whether or not we continue to land (that's the meaning of the famous, out-loud 'Decide!' call that echoes out in the cockpits of certain aircraft) is determined by what we can see when we reach the specified minimum altitude or height."

Decide!

So what, exactly, does a pilot need to see when they are at the decision point?

"What are known as the 'visual reference requirements' depend on the level that the instrument approach is certified to. In some cases, we need to see just three consecutive lights, but also a 'lateral', or side-to-side, lighting element. On other approaches we need to see only one light—but it has to be a centerline light of the runway."

"And for a fully automatic landing, in fog, for example, we may not be required to be able to see anything at all before touchdown. But there is still a minimum visibility requirement for landing. We need to be able to see enough to taxi, manually, off the runway," Vanhoenacker explained.

I'm glad Vanhoenacker is at the controls.

Mike Arnot is the founder of Boarding Pass, a New York-based travel brand, and a private pilot who loves to fly and land at night.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app