How do pilots know how much fuel to take on a flight?

Vehicles don't tend to get very far unless you give them some juice. Lorries need their diesel, cars need their gas and a Tesla needs its electricity. These vehicles all travel relatively short distances. So how do you fuel a vehicle that travels halfway around the world over areas where filling up isn't possible? Let's take a look.

Where Do Aircraft Store Their Fuel?

While the wings of an aircraft are primarily there to create the lift to make it fly, they also contain a hidden secret. To save weight, the wings are mainly hollow, reinforced by clever structures to keep their strength. It's this hollow space that is utilized as the fuel tanks. Some aircraft, like the A380, have complex fuel systems using multiple tanks situated not just in the in the wings but also in the belly of the aircraft and toward the rear. Others, like the 787 Dreamliner, which I fly, have a more simple system of a tank in each wing and a center tank in the belly. When the aircraft is being prepared for a flight, fuel is pumped into the aircraft wing where a logic system directs it to the tanks where it is needed. This normally entails filling the wing tanks first and then sending the rest to the center tank.

Where Does the Fuel Come From?

At smaller airports with smaller aircraft, you may recall having seen a fuel tanker. This looks like a giant lorry of fuel, which is driven up to the wing and then used to fill the tanks. However, for bigger aircraft, many of these lorries would be required to uplift the fuel required, taking a lot of time. Instead, a smaller truck arrives, which is in effect a mobile pumping unit. It connects to a fuel hydrant in the ground, which is then connected via a series of pipes to the airport's central fuel storage. Fuel is then pumped under pressure directly into the aircraft.

Do Aircraft Use the Same Fuel That I Put in My Car?

While the unleaded gas that you put in your car also comes from oil, the fuel that goes into an aircraft is somewhat different. You may remember from your GCSE Chemistry (of course you do, right?!) that the raw oil is heated in a refinery. These vapors then condense into liquids at different temperatures. The resulting liquids form the base of fuels such as gas, diesel and kerosene. For jet fuel, kerosene is the fraction of choice for a number of reasons. First, it has a much higher flash point than gas, commonly around 464°F. Commercial aviation is all about safety, and this includes the fuel. When you're carrying tens of tons of fuel, you want it to be as stable as possible. This means that in the event of an accident, the fuel is less likely to ignite. Second — and most importantly from a day-to-day aspect — it has a very low freezing point. While you're seated enjoying a glass of vino in a pleasant 70° F cabin, outside your window it's a bitterly cold — about -67° F. In higher latitudes it can get even colder — -97° F over Siberia is my personal record. When temperatures get this low, a conventional fuel would freeze. The Jet A-1 powering the engines has a freezing point of -53° F.

Why doesn't it freeze when it's regularly -67° F outside but the fuel supposedly freezes at -53° F? Because when fuel is loaded before the flight, it's normally at the ambient temperature. Take an average spring day out of London where it's 60° F. For this example, let's say the fuel is also 60° F. As the aircraft climbs, the outside air temperature decreases. Nominally by 3.5° F every 1,000 feet. This means that by the time it reaches 35,000 feet, the outside temperature will be -67° F. This is called the Static Air Temperature, or SAT. This is the temperature you'd feel if you were just relaxing on a passing cloud. However, if the fuel in the wings was to reach this temperature, it would freeze and cause serious problems for the engines.

Here's where physics comes to our assistance. If the aircraft was just sitting on that cloud with you, the surfaces would chill to -67° F, as would fuel in the wings. However, the aircraft isn't stationary. It's flying through this cold air mass at hundreds of miles per hour. The speed of air over the wings creates friction, which actually heats the surfaces. (The composite structure of the 787 Dreamliner wing means that it cools far slower than a conventional aluminum wing.) By knowing the airspeed, you can work out what this heating effect will be. Adding this value to your SAT gives you your Total Air Temperature, or TAT. It is this TAT value that is chilling the wings, and thus affecting the fuel temperature. The wing material also has an affect on this chilling.

If I was to tell you that a typical TAT value at 38,000 feet is just -6° F, you'll now be able to understand why the fuel doesn't freeze.

What Happens If the Fuel Temperature Gets Close to -53° F?

It is possible that, if flying for prolonged periods in extremely cold air masses, the fuel temperature could drop toward the freezing point. However, pilots are alert to this possibility and will take proactive steps to ensure that this doesn't happen. Each aircraft type has a threshold at which the crew are alerted to a low fuel temperature. On the A320 family, that threshold is around -22° F. If this happens, the crew have options. Either fly faster to increase the heating effect of the air, or descend into warmer air. Since aircraft tend to fly as fast as they are designed, normally the only viable option is to descend.

Flight Planners: The Brains Behind the Scenes

We all know that filling your car up is one of the most expensive things you do in your working week. It takes a large chunk out of your budget, and that's no different for airlines. Each year, easyJet spends around $1.8 billion on fuel. That's 32% of its cost base. A massive amount of money. As a result, airlines know that if they can keep their fuel costs down, their profits stand a better chance of going up. Consequently, a large amount of time and effort is spent on finding ways to both reduce the price paid for this commodity and also how much the aircraft then use. The more fuel an aircraft carries, the heavier it becomes. The heavier the aircraft, the more fuel it needs to fly a given distance. In other words, you're actually burning fuel just to carry the fuel you need to get to your destination. As a result, there is an optimum fuel load that will get us to our destination but without wasting too much fuel just carrying it.

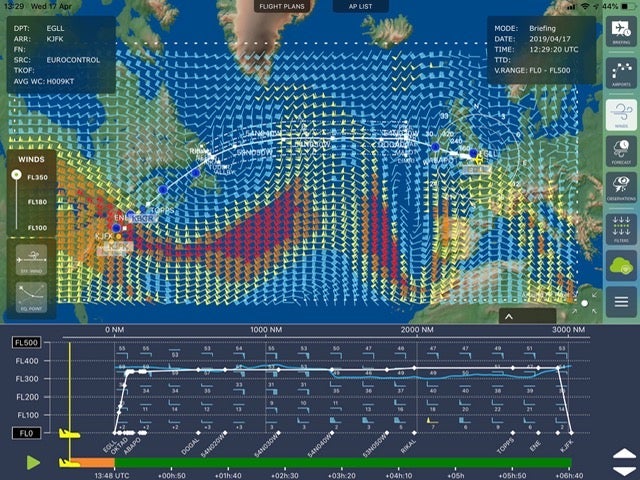

Let's imagine you're operating a flight from London to New York. Before the you report for duty, the planning department in the airline's operations center will create a flight plan specific to your flight. They will take into consideration atmospheric conditions, airspace restrictions and aircraft performance factors, to name just a few variables. From this information, they can create the most fuel-efficient route for that flight on that date. This is why you may notice that your geographic route may often be different if you fly regularly between two cities. Once the route has been decided, the fuel required to get there is then calculated. For a given distance, this will vary depending on aircraft weight, planned cruising altitudes, wind velocity and air temperatures. This magic number is known as the 'trip fuel' or the 'burn'. In other words, the amount of fuel which the aircraft will use just to takeoff from London and land in New York.

However, if you were driving a car across a desert, would you take the absolute minimum you need or put a little extra in. Being the prudent, risk adverse driver/pilot that I know you are, you'd take a little extra. This is the same for aircraft. As part of the planning stage, several other fuel values are also calculated. First, you'll need fuel to start the engines and taxi out to the runway where you start the takeoff run. There are no prizes for guessing that this is called the 'taxi fuel'. Next, you're into the trip fuel as mentioned above. But what if things don't go according to plan?

The North Atlantic is a very busy route. Sometimes, we may not get the crossing altitude on which the flight plan and trip fuel were predicated. This will result in more fuel being used to fly the same distance. Crossing the equator, there are often large bands of thunderstorms that we need to avoid. This can result in hundreds of extra miles flown and also where the contingency fuel comes in. Normally, that's 5% of the trip fuel, though it can be reduced (or increased) based on statistical data collated by the airline. For example, aircraft arriving at London Heathrow are quite often subject to delays. In order to do this, they fly around a holding pattern. This uses fuel that is not accounted for in the trip fuel. Over time, airlines can build up an accurate picture of how much fuel their aircraft use for a given flight and adjust the contingency accordingly.

Always Have Backup Plan(s)

So you're cruising across the Atlantic at a lower altitude than you planned. The headwinds are also a stronger than expected. To make matters worse, air traffic control has changed your route to a longer one. You've checked the New York weather and there's been a freak snowstorm and the delays are building. But it's ok — this is what your contingency fuel is for. Throughout the flight, you're constantly monitoring your fuel status to ensure that you have enough to reach New York. But what if you're going around the holding, waiting to land when they close the airport? You've used most of your trip fuel and your contingency fuel has been used up, too. What now? Time to utilize the diversion fuel.

All flights must carry separate fuel that enables them to fly from the planned destination airport to another airport where they can land safely. Depending on geographic location and weather, this may be an airport a few miles away. Or, in the case of islands like the Seychelles, the diversion airport could be several hours away. Although not abnormal, it's quite rare for an aircraft to divert. In 12 years of flying, I've diverted just a handful of times. The skill of a good crew is to make the decision to divert before reaching the minimum diversion fuel level.

As you've seen so far, commercial aviation is all about having a backup plan. It's even about having a backup plan for your backup plan. But what if your backup backup plan (still with me?!) isn't good enough. You have one more plan. Final reserve. In the entirety of their career, most pilots will never get to this stage of fuel. If you have exhausted your taxi, trip, contingency and diversion fuel but still not have been able to land, you're having a really bad day. In this situation, the final reserve is there to save you. Providing 30 minutes flying time, it's there to get you on the ground at any suitable airfield having declared a fuel emergency. It's only there for emergencies, and pilots must never plan to use this fuel. It's the final 'Get Out of Jail Free' card.

If a crew were to eat into their final reserve fuel, a thorough investigation would be carried out by the company and regulating authority.

The Pilot's Decision

When you add up the trip, contingency, diversion and final reserve figures, you arrive at the 'required fuel' — the minimum amount with which the aircraft is allowed to depart. That said, it's not the amount which with it has to depart.

As part of the preflight briefing, the pilots will discuss all the factors that could influence how much fuel is really needed. Delays on departure, thunderstorms en route and bad weather on arrival may all suggest that it would be pertinent to take extra fuel. When all the factors have been considered and discussed, the crew will decide on a final fuel figure, which will then be loaded into the tanks.

Bottom Line

Fuel doesn't end up in an aircraft by chance. Every step of the process has been carefully assessed, controlled and checked. Right from using a fuel to suit the physical environment at 38,000 feet, to making sure that there will always be enough fuel on board to cover all eventualities.

Commercial aviation is all about safety. While you're seated, enjoying a film or having a sleep, your pilots are constantly evaluating and re-evaluating the current — and future — situation. By having multiple backup plans, we ensure that you are kept as safe as possible, allowing you to rest easy.

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app