Can planes fly in thunderstorms? Here's what a pilot says

Last week thousands of flights were canceled across the U.S. due to severe thunderstorms. It's frustrating for both passengers and the airline crews who also have families and social events to get home to themselves.

When it comes to Mother Nature, though, thunderstorms are not to be messed with. In addition to lightning, there are a number of factors pilots must take into consideration before deciding to fly near them.

[table-of-contents /]

Problems with thunderstorms

Severe turbulence

Thunderstorms form due to a combination of moisture and rising air. As this rapidly rising air in the thunderstorm cloud runs out of energy — sometimes as high as 50,000-60,000 feet above the ground — it has to come back down at some point. The result is a maelstrom of rapidly changing winds within the storm cell. The strength of the changes in wind direction can have dramatic effects on an aircraft.

These conditions won't cause an aircraft to crash, but they're certainly strong enough to cause serious discomfort to passengers. Severe turbulence can cause items as heavy as drink carts to become airborne, which can seriously injure those on board.

Strong winds

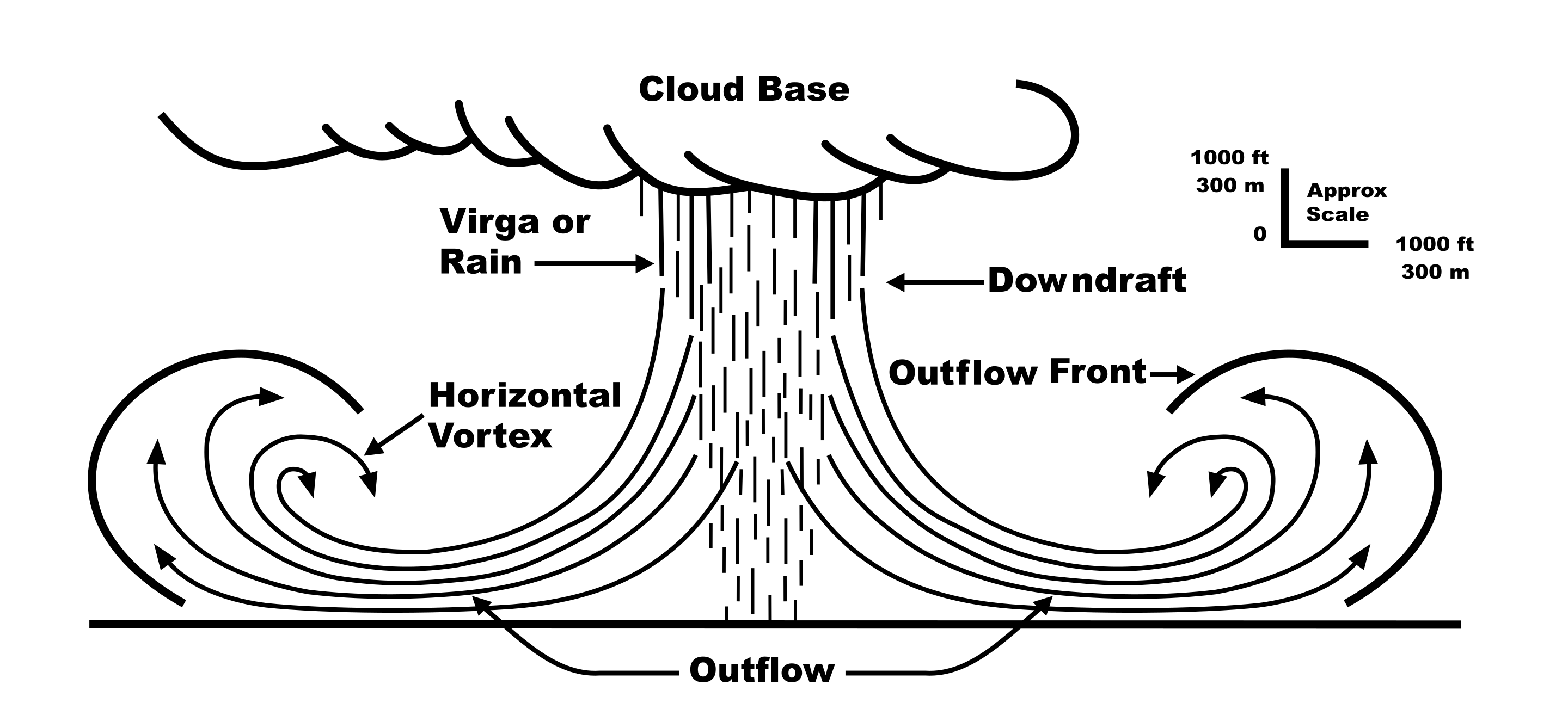

In addition to rising columns of air, moisture picked up from the surface moves inside the cloud. As this vertical energy runs out, it cools in the colder temperatures aloft. The moisture then falls to earth as rain or hail, creating the brief but intense showers you experience on the ground.

As it falls, it creates downdrafts of air to the earth. When these downdrafts hit the surface, they have nowhere to go but outward. Think of pouring a glass of water onto the floor: As the water hits the ground, it splashes outward. If you keep pouring the water, the splashing isn't uniform. Sometimes it goes farther in one direction, other times not so far.

It's the same with the wind. As it hits the surface, it spreads out at different rates. It's this difference in speed that creates the gusts. As the thunderstorm cloud moves across the ground, these gust fronts push out ahead of the cloud, giving a good indication that a thunderstorm is imminent.

For pilots, this change in wind speed and direction can create wind shear, which can be a threat to aircraft.

Heavy rain

Stopping a 200-ton airplane safely on the runway takes accurate calculation and effort by the pilots. Similar to driving a car, an aircraft stops more efficiently when the runway surface is dry. The more flooded it becomes, the less effective the brakes are.

When too much water builds up on the surface of the runway, the aircraft's tires can lose contact with the surface in a phenomenon known as hydroplaning. This can massively reduce the brakes' effectiveness.

Runways at most large airports are built with grooves cut into the surface and angled off to the sides so that the runway's center is actually higher than the edges. This helps drain excess water from the paved surface, reducing the chances of hydroplaning.

How do these elements affect flights?

The safety and comfort of our passengers are every pilot's prime concern. Because of this, avoiding the effects of thunderstorms is high on our agenda. The best way to do this is to avoid thunderstorms altogether.

During the day, some storms are easy to spot. However, at night, or when the storms are shrouded by other clouds, they're not so easy to identify. For these instances, we use our weather radar.

Weather detection on an aircraft is based on a transmitted energy beam hitting water droplets in a cloud and then bouncing back to the aircraft. As water droplets vary in size and density, the more dense the water droplet, the greater the radar return.

As a result, particularly dense water droplets such as hailstones will have a greater return than less dense droplets such as fog. These returns are then depicted in the flight deck on the navigation display. Green areas are those with low returns and red indicates areas with high returns.

Most weather radar systems on newer aircraft also feature a turbulence detection function. This uses the Doppler effect to detect the movement of the water droplets and areas of turbulence are depicted on the screen in magenta.

Storms en route

When we've identified a thunderstorm on our route, we try to determine the best way to avoid it. Normally we'll attempt to fly upwind of the storm, as the downwind area tends to be the bumpiest. However, when there's a line of storms dotted across our path, this may not always be possible.

Once we've decided on our preferred route, we must ask air traffic control to confirm our new route will keep us clear of other aircraft. The problem comes when there are extensive thunderstorms in a relatively small geographic area and multiple aircraft are trying to deviate around them.

When ATC has 50% of the airspace to fit in 100% of the aircraft, there's an obvious challenge. To avoid this, ATC restricts the number of aircraft in their sector. This helps ensure that they are all safely separated at all times.

Obviously, once an aircraft is in the air, there's no way to make it wait. Because of this, ATC predicts how the forecast weather will affect the flow of traffic during the hours ahead and issues delays to aircraft before they leave the gate.

This is why only a handful of flights from a certain airport may be delayed due to weather while all the others are able to leave on time. The bad weather causing your delay may not be outside your window, but it could be hundreds of miles away along your route.

Storms near an airport

Storms en route tend to be relatively simple to deal with from the pilot's perspective, even if they do cause headaches for ATC. However, storms near or over an airport pose much more of a threat and logistical problems for those of us flying the aircraft and our colleagues working on the ground.

On the ground

For those people working hard on the ground to load and unload bags in the aircraft holds, prepare the aircraft for its next flight, pump fuel into the wing tanks and empty the aircraft toilet waste tanks, lightning from thunderstorms is a real threat to their safety.

When lightning is detected nearby, most airports mandate closing the ramp area. This means that all the time-critical jobs that need to be completed before a flight can depart are put on hold until the storm passes.

This not only delays the outbound flight, but it can also cause knock-on delays for inbound aircraft waiting for that gate.

There is currently no centralized guidance for airports in the United States to determine when and how long the ramp should be closed in these situations. Some airport decision-makers use data as rudimentary as hearing thunder and waiting a certain time period until the lighting was last observed before opening up again.

However, many bigger airports have sophisticated equipment installed around the airfield. This equipment can detect lightning and accurately pinpoint where it occurred and how much of a threat it is to the airport.

On departure

Takeoff is one of the most safety-critical stages of the flight, so the effects of any adverse weather such as thunderstorms must be taken into account. In these situations, it's the threat of wind shear that can cause the biggest delays for flights.

An aircraft is at its most vulnerable when it's flying at slow speeds, particularly in the moments just after it gets airborne. If it were to encounter wind shear, a sudden and severe change in the direction or speed of the wind, there is a risk that the wings would no longer be able to generate enough lift to keep it flying.

Because of this, if there are thunderstorms around the airfield on departure and the pilot believes they might be a threat in those early stages of flight, the pilot tells ATC they shouldn't take off at that time.

This may even mean lining up on the runway and taking a good look at the weather radar in the direction that we're departing. If there's a storm cell sitting over the departure end of the runway, or in our initial routing, we will inform ATC.

Depending on other aircraft waiting to depart, this may mean sitting in place until such time that we feel comfortable enough to go, or taxiing off the runway to allow another aircraft with a different routing to get airborne. This is something I've done many times in my career.

On approach

As the aircraft nears the ground, any changes to its flight path can quickly become a serious threat to its safety. Once again, wind shear is a major threat.

As we near the airport, we keep a constant eye on the weather radar and listen to other aircraft on the radio to find out their experience on the approach. Before starting the approach we always make sure that we can do so without the risk of being affected by the storm. Or, if we do encounter it, we make sure to have a plan for a safe way to escape.

Wind shear has been a threat to aircraft for several decades, so much so that aircraft now use the weather radar system to detect it. If the system detects a hazardous situation ahead, it alerts the pilots with an audio and visual warning, either instructing them to avoid the area of wind shear or to perform a go-around.

More often than not, if there is any doubt about making an approach, pilots will take up a holding pattern well clear of the weather and wait until it has passed and it's safe to make an approach. If this takes longer than expected, they may have to divert to another airport where a safe landing is assured.

Another threat comes from heavy rainfall.

Before each landing, we calculate how much runway we will need to stop at our expected landing weight in the expected weather conditions. This is affected by the temperature, wind strength and direction and also how slippery the runway is.

If we know how slippery the runway is, we can factor this into our landing distance calculation.

The problem comes when a thunderstorm has dumped a massive amount of water on the runway in a short amount of time and the actual surface conditions are worse than reported by ATC. In these situations, there is a very real risk of not being able to stop in time and going off the end of the runway.

As a result, if there's any doubt as to the surface condition of the runway, we will either take up a holding pattern until its state can be verified or divert to another airport.

Bottom line

When it comes to safety, pilots and ATC do not take any risks. If a flight needs to be delayed because of the weather conditions, your pilots will not hesitate to do so. We understand that it's frustrating for our passengers. However, we're there to get passengers safely to their destination, even if it is several hours late.

As the pilot's saying goes, "It's much better being on the ground wishing you were up there than being up there and wishing you were on the ground."

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app