Air Force One to Coach Class: How US Government Workers Travel

Kar Chu, a longtime Department of Defense employee who's been at the US Navy base in Yokosuka, Japan, since 2016, was just transferred to Germany. And like many government workers who travel for work, he's been worried about it.

"Travel has been one of the things on my mind," he admits.

Chu, who has also worked for the Department of Homeland Security, has become something of an expert on the workings of the sometimes-Byzantine federal rules and regulations that government workers have follow when traveling on government business.

And with government shutdowns becoming more frequent, more and more people are turning to experts like him with two questions: How do government officials travel for work, and who's paying for it?

There's good news and there's bad news. The good news is that the paramount concern in most cases of government travel, at least on paper, is ensuring that taxpayers aren't on the hook for too much of the bill. There's even a special partnership program that gives government workers access to cut-rate flights, and another that tells them exactly how much they should be paying for a trip.

The bad news? The rules can be confusing, opaque and ill-defined.

You could see both the good and the bad in how Chu had to buy his tickets to Germany. Chu wasn't able to get a direct flight from Narita (NRT) to Frankfurt (FRA) that the federal government would be willing to pay for. Instead, the government offered him several fares ranging between $1,200 to $1,400, on a US carrier, that would involve taking three separate flights via stops in two major US cities. He would've finally arrived at Ramstein Air Base nearly two days later.

His other options included more expensive flights on Scandinavian Airlines and Qatar Airways, costing between $2,000 and $2,400, that arrived in Frankfurt via Copenhagen (CPH) and Doha (DOH). The most expensive option, a direct flight from Narita to Frankfurt on Japan Airlines, cost more than $4,300. He ultimately bought two tickets through an online budget travel agency on Japan Airlines for a total of $2,764, instead.

As with many business travelers in the private sector, the process involves laying out the money for the trip up front, filing expenses when he gets back, and his employer reimbursing him after his invoice is approved. Appropriate officials get a government travel card, which they're expected to pay off like a credit card — kinda. But more on those later.

Foremost in Chu's mind the whole time: The government has no obligation to compensate him for anything above their recommended lowest-cost fares.

"The government option values price over speed," Chu said. "In my particular case, I asked them to find me the shortest time, because I was bringing a cat and dog who could not fly long distance. If I take any price besides the lowest price available, I may be on the hook for the difference, or even the entire amount."

Rules are rules — until they're not

For traveling government workers, there are six letters that guide their lives. The Bible of work travel goes by the initials "FTR." And the high priest? "GSA." The General Services Administration oversees the Federal Travel Regulations, the rules that govern how Title 5 federal employees are allowed to travel. Title 5 employees include the vast majority of federal civil servants.

Federal legislators and the Supreme Court have their own separate sets of rules that regulate each branch's travel — key among them the rule that congressmen aren't allowed to use government resources when they're campaigning or doing anything that isn't strictly for government business. (Official congressional travel looks a lot like FTR travel outside the campaign rules, though.) They're only allowed to take advantage of the government rate when they're on official trips, but legislators are allowed to use award flights and loyalty-program points and miles at their own discretion. When government officials or legislators have to travel to war zones or other dangerous areas — like to meet with soldiers, Marines and airmen at a US military base in Afghanistan, for example — the journey naturally may entail flying aboard military transports. But even those trips aren't immune to bickering about what constitutes genuine government business.

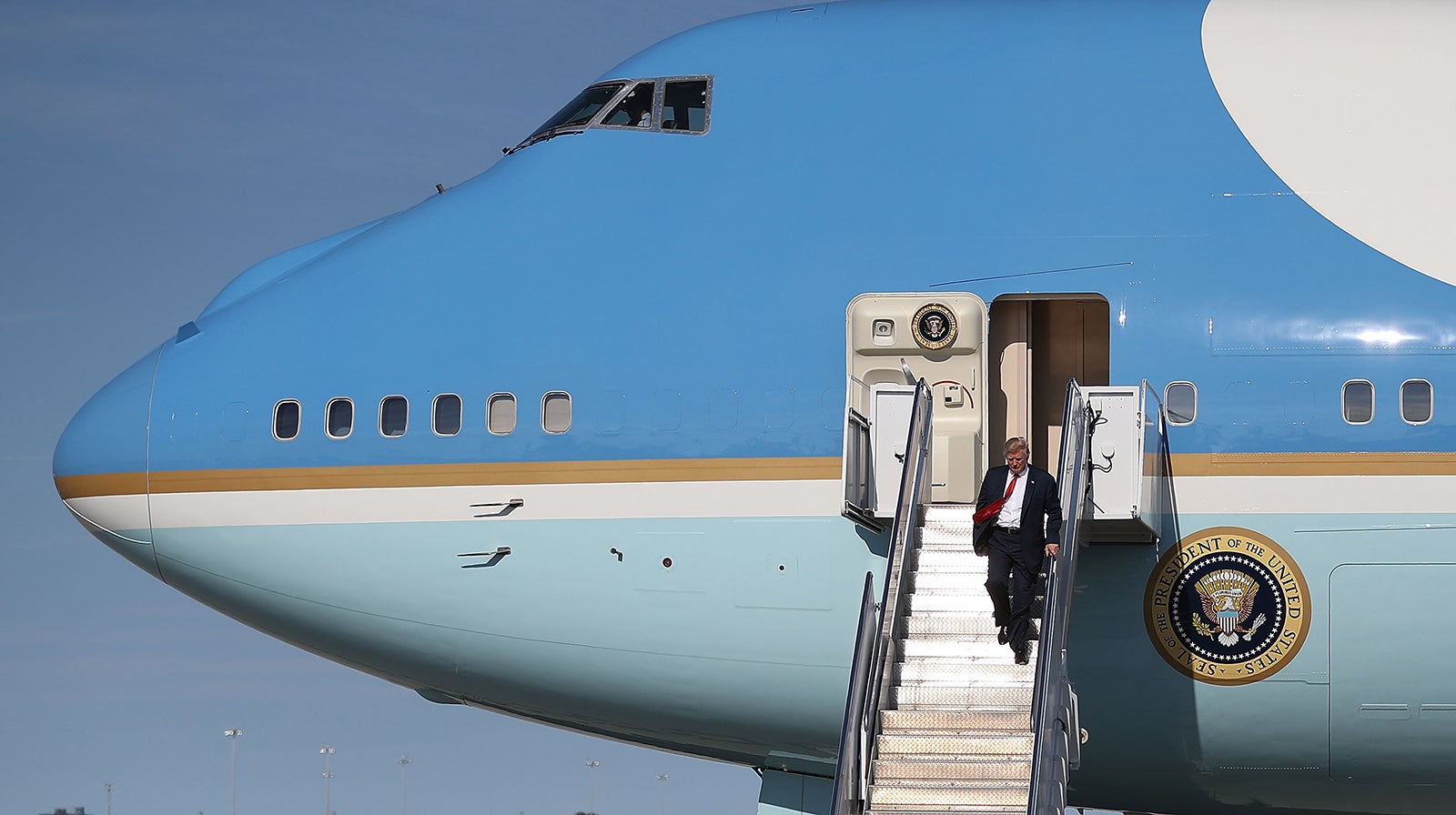

The president, of course, has Air Force One, but if he's campaigning for himself or another candidate, the appropriate campaign committee is supposed to foot part of the bill — though the decades-old rules about who covers what are arcane and controversial.

For Chu, getting the government's lowest fare wasn't possible because of his pets, but it also was the most arduous option, meaning he'd have had to take that nearly two-day trek across three continents. Instead, he's going to have to hope the government OKs the rate for his more expensive — but more humane — flight.

On the plus side, government workers have access to a travel tool that isn't available to the general public. The GSA's City Pair Program has low-cost flights with carriers in hundreds of cities on thousands of routes throughout the world. Workers find out what rate they're entitled to on the government website, then can plug their codes into the airline's site for the discount. (They're required to verify their government employment to get the lower rate, of course.) For fiscal year 2019, the government has contracted with carriers such as Delta, American, United, Southwest, Alaska and Hawaiian. More frequently, they'll use their agency's electronic travel system to book their travel directly. Agencies also can contract with corporate travel agencies for more complex bookings when needed (such as international trips).

Officials tout the many advantages that government workers have over civilian travelers if they book with the help of CPP, including rates that are "considerably lower than commercial fares, saving the federal government billions of dollars annually," according to the GSA website. The purchases are fully refundable, with last-seat availability, stable prices and no blackout periods.

It's not perfect, and there are still internationally based government employees who can't get low-cost, nonstop rates. CPP has no low-cost direct flights from Tokyo to Frankfurt or to Paris, among other European cities, for example. But if Chu had been transferred from Tokyo to Chicago, he could have purchased a direct flight on United Airlines for $550.

Where officials get in trouble for travel

Of course, there's a catch even when it does work: Government officials with extensive knowledge of the FTR said that federal workers are generally forbidden from traveling in business or first class, with exceptions made only for those with medical conditions or certain disabilities.

For example, the DOD's Other Than Economy-/Coach-Class Transportation worksheet states that those flight classes, "due to a medical disability/special need, may only be used when there is no other means to accommodate a traveler's condition, such as bulkhead/aisle seating or use of two adjoining seats. A traveler's condition must be certified by a competent medical authority and authorized by an Other Than Economy-/Coach-Class Transportation-authorizing official."

In other words, getting a premium seat isn't easy even when you have a legitimate medical condition and are fluent in bureaucratese.

"I never flew anything but coach nor have I heard of anyone — minus Trump cabinet members — who flew business or first class," Chu said.

Which, let's face it, has been a problem. Trump Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price resigned in 2017 after it was reported that he used private aircraft at taxpayer expense for domestic travel. Former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, former Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin have all also faced scrutiny involving their own use of chartered flights at exorbitant cost.

But it's not just the VIPs who have gotten in hot water with their federal travel-expense misdeeds. In 2018, a government spending bill banned US troops and civilians working for the DOD from using government funding and expenses incurred in casinos or strip clubs after it was revealed in a DOD inspector general's report that employees had plunked down more than $950,000 on the government dime in casinos and nearly $100,000 in adult-entertainment clubs.

Which brings up those government travel cards that are kind of like credit cards but also not.

"The place where countless people get in trouble is using your government travel card, which is basically just a credit card for nonauthorized expenses, and then not paying it off," Chu said.

Officials said that these cards don't allow workers to maintain a revolving balance.

"These are individually billed cards, in that sense they're not really credit cards," said one government official, who asked that her name not be used because she wasn't authorized to speak with the press. "They must pay their balance in full."

And for points-and-miles geeks, there's another big downside.

"I've always had a government travel card for expenses in DHS/GSA/DOD," Chu said. "It's unfortunate, because I could be getting 3x points with my Chase Sapphire Reserve."

"In the rare chance you can travel with points or mileage, it wouldn't benefit the travelers, since the government only reimburses you for the actual price paid and they can't pay you back in points," he added. "You can, however, keep other benefits that aren't tied to price, such as frequent-flyer miles or hotel-stay programs."

For official travel, the government allocates a per diem that allows for hotels, meals and some personal expenses. The standard lodging rate for most government officials is $94, but that rate can increase or decrease depending where and when you're traveling. For example, the lodging rate is $288 if a worker is traveling to New York City in December.

Each agency has the power to set their own rates for employees, according to the same official, but they can't do it willy-nilly. Per diems can be no more than 300% of the FTR rate. So an agency could raise a $150 lodging per diem up to $450 if no lodging were available in the city at the standard FTR rate.

But officials said that the reality is that government workers don't really have as much leeway to abuse the system as the public might imagine. More frequently than not, agency per diems are more restrictive than the standard FTR rate. And if a worker exceeds his or her allowance, he or she is on the hook for what the government doesn't cover.

"You can stay at the Taj Mahal," said a second government official, who also asked not to be named. "But the government only reimburses what is actual or necessary."

And during a government shutdown, one of the first things to be struck off the list of absolute necessities is travel for almost all government workers. If the government is shut down again, all nonessential travel is completely discontinued, and workers are flown home immediately — whether or not their work has been completed.

"If you are away from home and a shutdown is imminent, you will be sent home a day or two prior," Chu said. "If you are in a remote location for work or training, you will leave, whether it is finished or not, and return to your home of record."

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app