Insider Series: Are US Aircraft Safely Maintained?

New to our Insider Series (where travel-industry professionals write about their work under pseudonyms), TPG Contributor "Marty McFly," a pilot for a major American airline, shares his thoughts on aircraft maintenance in the fleets of domestic carriers.

Of all the choice comments I overhear from passengers awaiting delayed flights, the ones that confuse me most are complaints about 1. the weather (airlines still haven't invented a "weather off" switch), and 2. aircraft maintenance. The latter is especially perplexing to me, as when I'm on board a jet — either as a passenger or working crew — I want to be in a fully functioning and safe machine. When a maintenance delay occurs, I'm thankful that not only was the issue found, but that the discrepancy is going to be repaired before we break the surly bonds of Earth.

In my entire career as a pilot, I've experienced only a handful of (very manageable) equipment malfunctions that ranged from a jammed flap to an engine failure, and in each case, my crew was well trained to handle the situation and the back-up systems worked as designed. However, a recent Vanity Fair article questioned the maintenance practices of a majority of the airline industry when it highlighted the outsourcing of heavy aircraft checks to foreign maintenance facilities. This practice is sadly one of the hangovers of the financial meltdown of the early 2000s that severely impacted the airline industry. During that era, many airlines used employee contract restructuring, both in and out of bankruptcy, to allow for more outsourcing of maintenance to subcontractors.

Many of these maintenance subcontractors are in Mexico, El Salvador and China, among other countries. I don't doubt the professionalism of the subcontractors employed in these foreign facilities, but I'd rather all of the maintenance be done in-house by employees of the airline — I simply have more trust in the mechanics who are part of an airline's family than I do in outsourced employees.

That said, subcontracted maintenance facilities are inspected by the United States FAA, their procedures are approved and certified by the aircraft manufacturer, and individual airlines will have representatives present to provide additional oversight. Additionally, pilots fly each aircraft that has undergone maintenance and test all its aircraft/backup systems before it's returned to service.

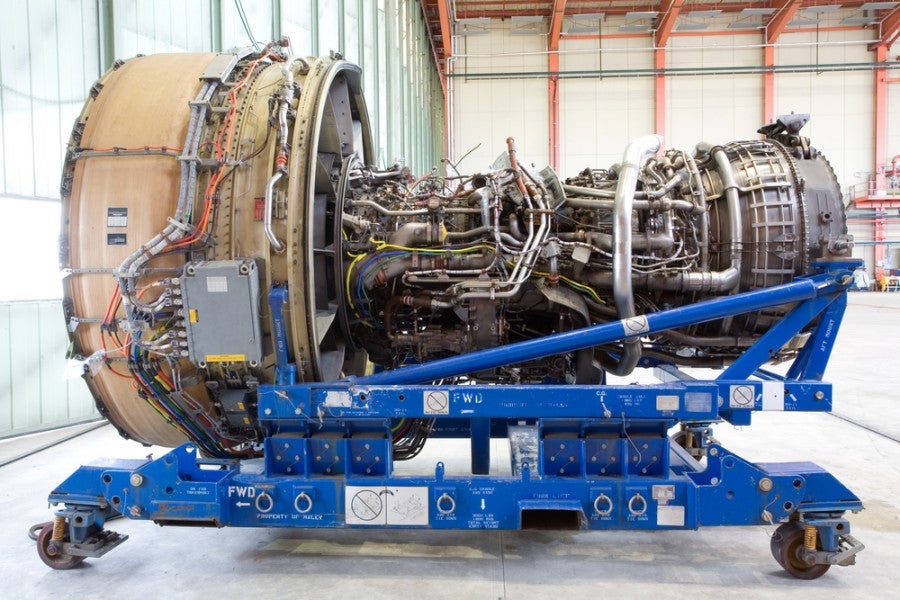

The bulk of the work performed at subcontracted maintenance facilities are Heavy Maintenance Visits (HMV), which are also called "heavy checks" or "D" checks. Done about once every six years, an HMV check is essentially a complete tear-down of the aircraft during which every aircraft system, flight control, tube, wire and cable is checked for functionality and continuity. These checks can take more than a month to complete and cost well over one million dollars.

Additionally, each airline has its own FAA-approved maintenance schedule that complies with the manufacturer's maintenance guidelines. While an airline may vary the timing of certain checks, airline maintenance facilities know that the following required checks must be done without exception:

"C" checks are performed every 20-24 months or after a manufacturer-designated number of flight hours. The primary focus of these checks, which take about two weeks to complete, is an aircraft's major control systems — hydraulic, electrical, pneumatic and emergency — to ensure they don't require repair or replacement.

"B" checks are done every three to six months or a predetermined number of cycles (take-offs and landings) or flight hours. These checks are less intensive and usually require visual inspection of flight systems and checks of systems quantities like oxygen, hydraulic fluid levels and other miscellaneous items. Some carriers don't do B checks but instead incorporate the required inspections as part of the A or D check.

"A" checks are done regularly and usually completed at least once a month. They're designed to test the functionality of an aircraft's brakes, hydraulics, electrical, emergency lighting and crew/passenger oxygen systems. These systems aren't torn down like in a D check, but are instead simply tested for airworthiness.

Aircraft engines are also on a rigorous inspection schedule that's often different from the aircraft as a whole, as engines are often swapped from one aircraft to another as they're found to need repair and replacement. In regards to every other part, system, etc., airlines and manufacturers are in constant communication in order to alert each other to frequent maintenance issues on specific aircraft types.

The one check that's done before every flight is the walk-around by maintenance and flight crews. The exterior is inspected for bird and lightning strikes, ramp damage, missing screws, tire pressures, tire-tread wear, as well as the general overall condition of the aircraft. The pilots also run a number of pre-flight tests of the aircraft systems in the cockpit before each flight.

Since any broken item on an aircraft — from tray tables to bathroom lights — essentially "breaks" the entire aircraft, the manufacturer creates a minimum equipment list that designates what permits the aircraft to safely operate with passengers on board. This list is certified by the FAA for each aircraft and includes the mundane (e.g., overhead reading lights) to the slightly more important (e.g., standby systems for larger aircraft). Individual airlines will often create their own minimum equipment lists, which may be more restrictive (but not more permissive) than the manufacturer list.

Ultimately, the decision to fly an aircraft with broken, disabled or missing items falls to the dispatcher and flight's captain and crew. For instance, an inoperative anti-skid braking system may be deferred for future maintenance, as the crew flying to an airport with long runways and good weather may be completely confident that they can safely operate that flight with an inoperative anti-skid system. However, a different crew may not accept the same aircraft because the runway they're flying to or weather they'll be operating in may not allow for the highest level of safety without that anti-skid system.

I often point out that the maintenance on an airplane is infinitely more thorough than the maintenance on your car, and most people don't think twice about driving at high speeds in any kind of weather and surrounded by people in cars who may or may not maintain their car. Personally, I feel a lot more comfortable in my jet — and I want to get home safely just as much as you do.

[card card-name='Chase Sapphire Preferred® Card' card-id='22125056' type='javascript' bullet-id='1']

TPG featured card

at Capital One's secure site

Terms & restrictions apply. See rates & fees.

| 5X miles | Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel |

| 2X miles | Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day |

Pros

- Stellar welcome offer of 75,000 miles after spending $4,000 on purchases in the first three months from account opening. Plus, a $250 Capital One Travel credit to use in your first cardholder year upon account opening.

- You'll earn 2 miles per dollar on every purchase, which means you won't have to worry about memorizing bonus categories

- Rewards are versatile and can be redeemed for a statement credit or transferred to Capital One’s transfer partners

Cons

- Highest bonus-earning categories only on travel booked via Capital One Travel

- LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Enjoy $250 to use on Capital One Travel in your first cardholder year, plus earn 75,000 bonus miles once you spend $4,000 on purchases within the first 3 months from account opening - that’s equal to $1,000 in travel

- Earn unlimited 2X miles on every purchase, every day

- Earn 5X miles on hotels, vacation rentals and rental cars booked through Capital One Travel

- Miles won't expire for the life of the account and there's no limit to how many you can earn

- Receive up to a $120 credit for Global Entry or TSA PreCheck®

- Use your miles to get reimbursed for any travel purchase—or redeem by booking a trip through Capital One Travel

- Enjoy a $50 experience credit and other premium benefits with every hotel and vacation rental booked from the Lifestyle Collection

- Transfer your miles to your choice of 15+ travel loyalty programs

- Top rated mobile app